Samuel Mockbee, Rural Studio

September 8, 2013

Because of my long time interest in low cost housing, I kept coming across the name of Samuel (Sam/Sambo) Mockbee, associated with Rural Studio, Auburn University, in connection with the housing for poor Black communities in Hale County in Alabama. This was not an association I expected to come out of USA and decided to look into this unexpected phenomenon in more detail.

Because of my long time interest in low cost housing, I kept coming across the name of Samuel (Sam/Sambo) Mockbee, associated with Rural Studio, Auburn University, in connection with the housing for poor Black communities in Hale County in Alabama. This was not an association I expected to come out of USA and decided to look into this unexpected phenomenon in more detail.

This journey of discovery was exciting but turned sour when I heard of this remarkable man’s death from leukaemia at the age of 57 in 2001.

Europe is full of examples where architects, planners, philanthropists made significant contributions to develop social architecture (housing and schools) over last two centuries. Africa and Asia also saw some modest developments during late 20th century but the population, urban growth and poverty have given this problem urgency and much higher profile.

However, USA had no history of this ‘liberal–nonsense’, and for a white man to emerge in the heart of one of the most bigoted areas trying to ‘buck the trend’ was noteworthy.

This may be the right time to visit this man, his contributions and ambitions at the time when Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech is having its 50th birthday with consensus that dream has hardly come true.

Mockbee often quoted Alberti’s call for choosing between fortune and virtue, which he considered a question of value and principle. He thought architects to be by nature leaders and teachers, offering their ’subversive leadership’ for the shaping of environment, breaking up social complacency and challenging the power of status quo. He was repulsed by the thought that architectural profession was coming under the influence of consumer-driven culture and becoming part of the corporate world and corporations. For him architect should not wait to be told which problems need solution, architect should assert his own values that respect and are for the greater good.

“Architecture, more than any other art form, is a social art and must rest on the social and cultural base of its time and place. For those of us who design and build, we must do so with an awareness of a more socially responsive architecture. The practice of architecture not only requires participation in the profession but it also requires civic engagement. As a social art architecture must be made where it is and out of what exists there. The dilemma for every architect is how to advance our profession and our community with our talent rather than our talents being used to compromise them.”

Mockbee managed to disassociate himself from the bigotry of prevailing racial attitudes of American South and had a look at the effects of poverty and how architects can step over the threshold of injustice and address the true needs of neglected American family and their children who may also come of age without any vision of how to rescue themselves from the curse of poverty.

Mockbee once told one of his clients, a Catholic nun named Sister Grace Mary, that he’s not Catholic but “Christian by birth, Buddhist by philosophy, and heathen by nature”.

The main purpose of the Rural Studio has been to enable each student, tomorrow’s decision maker, to step across the threshold of misconceived opinions and to design/build with a ‘moral sense’ of service to community, being more concerned with the good effects of architecture then ‘good intentions’.

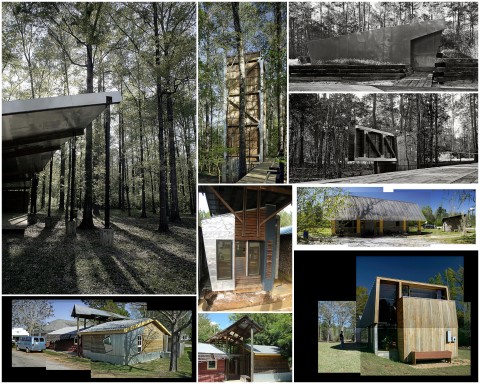

“On a triangular patch of land, next to the dirt road that serves as the hamlet’s arterial, stands a dramatic sculpture of glass and aluminum, cypress and steel and rust-red earth. This is the MasonsBendCommunity Center, designed and built as a thesis project by a team of fifth-year students at AuburnUniversity’s Rural Studio. The cost was approximately $20,000.

The building is processional in outline, gathering the community within arms of rammed earth, funneling them through a slender entrance sheltered by a fold of aluminum, and delivering them into a space that leads the eye through a fish-scale-glass membrane to the sky and trees beyond.” Chritine Kreyling

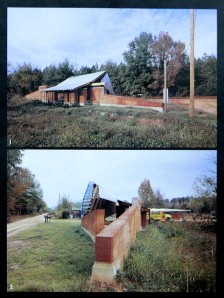

“Mockbee founded what is now called the Rural Studio, ‘Redneck Taliesin South’. Towards the end of his life he used to bring a group of his students to rural HaleCounty to design and build homes for the poor. One of the poorest regions in America, the county has more than 1,400 substandard dwellings, nearly all lacking electricity and running water. According to the 1997 Alabama County Data Book, about one-third of residents there live below the poverty level, with a per capita income just over $12,000 and an unemployment rate of 13 percent.

The Rural Studio not only fulfills an overwhelming need for decent housing but gives architecture students the kind of hands-on experience virtually all other educational institutions in the field lack. The houses are built for about $30,000 each using a variety of recycled and discarded materials (tyres, bottles) and funded mostly with grants from a local power company. Designed through a collaborative process involving students and local residents, the homes boast an unconventional modern flair that incorporates the cultural vernacular of the region. Lucy’s house made of 72,000 carpet tiles is now well known all over architectural community.

They may be cheap, but these are nice houses.” Mockbee thought that these should be good enough for him to live in with his family.

That Rural Studio is not only self-regulating, but it produces buildings of exceptional quality in direct response to the needs of the community, suggests that it has evolved from a teaching exercise to an alternative and compelling practical asset.

The New York Times published a feature on Rural Studio in December 2005 resulting in crowds of ‘camera/map carrying’ tourists seeking location of Mason’s Bend. With this kind of background the appearances start to matter, the church which was lacking frequent cleaning and was underused by the community became an embarrassment. This brought a changing attitude towards future community buildings and their future upkeep by apportioning responsibilities to various community members from start.

Freear wondered if Rural Studio has now reached its limit as a domestic housing endeavour, a well-intentioned educational experience benefiting a needy few, or could it evolve into a more serious and wide-ranging social project?

Projects are no longer conceived as isolated objects but links in a chain of essential social service.

The most recently completed final year projects exemplify this approach. Comprising a cell like lamella animal shelter, public park and hospital courtyard, rejuvenated as an attractive courtyard with expanded metal trellis serving staff.

Freear feels that he is also nearing his own limitations as a Director and recently started to take some classes at AA with an Indian architect Anapama Kundoo.

On a personal level looking back at the contributions Mockbee made fills you with admiration but its significance and impact on the root cause of poverty, resulting deprivation and alleviating it remains a mere ‘pin-prick’.

Suffice to say that few hundred houses and community buildings for a deprived community means a lot. However, the hope for me lies in the generations of young architects coming out of this ‘educational exposure’ with some idea of what ‘needs/survival’ really means to people they hardly knew existed.

I can only hope that even if some of them carry a small fraction of some of Mockbee’s generosity and wisdom the dream Mockbee had may be partly realized.

The information for this blog has been abstracted from Mockbee’s writings, interview and various magazine articles listed briefly below. The photographs are mostly attributed to my Flickr friends Ken Mccown and David Brown (odb). Their Flickr sites are well worth a visit.

Intereiew by Brian Libby April 2001; ‘Architecture without pretense’ by Christian Kreyling; ‘Community Hero’ by Jennifer Beck; Article by Andrea Oppenheimer Dean in Architectural Record.

Filed in Architecture, Architecture in USA, Indigenous Architecture, Modern Architecture, Regeneration, Self-Build Housing, Social Housing, Urban Renewal

Tags: Alabama, Anapama Kundoo, Andrew Freear, Aubern University, D.K. Ruth, Mason's Bend, Modern Architecture, Private Housing, Redneck Taliesin South, Sam Mockbee, Sambo Mockbee, Samuel Mockbee, Thomas Goodman