Smithsons’ buidings for University of Bath

July 6, 2011

Smithsons have earned themselves a very special place in 20th century British architectural world to sit on a high ledge and look back at their lifelong work consisting of some seminal buildings, influential and extensive writings and indeed some heartbreaking disappointments which almost drove them to despair.

Their final projects were built at Bath University campus which was founded in 1965 as a college of Advanced Technology based on a master plan by RMJM. I recently visited the campus for the first time to see Smithsons projects which are not very well known here as these were designed by them towards the end of their lives after a long and painful ‘drought’ of work. The architectural landscape of early 80s in Britain had changed and was dominated by new ‘superstars’ producing visually exciting stuff. The younger generation being taught by Smithsons failed to notice the pedigree and place of their new work in recent historical context being built around them. In fact, by this time most of the architectural world was not interested or impressed by what little they noticed in the press. Smithsons as usual were not to be swayed by the current fashions and in their normal defiant manner they took up the challenge to put their architectural legacy in rightful historical context with this last chapter they wrote and edited themselves.

Unfortunately, their good luck in obtaining this work in 80s coincided with another ‘drought’, this time financial, which almost decimated any attempt to produce buildings of decent standards to go with the growth demands of the campuses completed in the heady days of 60s. These campuses reflected the social and technological optimism of high hopes experienced by that period. The financial restrictions faced by Smithsons were bad enough but their insistence to ensure that their contributions were in keeping with their earlier intellectual aims made their life even more difficult. Although most of the ideas behind the master plan were derived from Smithsons/TeamX work but I feel that they were not entirely satisfied with this development as they clearly stated that they wanted to ‘…extend them and delicately shift their meaning.’

For Smithsons this opportunity to build meant “Almost a series of case studies. Each building could be a demonstration of different attitudes to location siting, and construction. Each could also show in built form both the development of formal, organisational or constructional ideas which had previously only existed in drawings for earlier projects, and the emergence of new thoughts related to the adaptation and extension of the fabric of existing settlements.” (From AJ article)

The Second Arts Building.

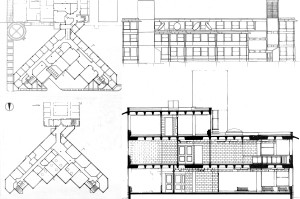

The second Arts Building was described by the architects as a new piece woven onto the edge of an existing mat… like a terminating fringe …seemingly complete. It is three storeys high and delta shaped in plan. A ‘knuckle’ lobby links this building to the older building next to a staircase. Three different departments were housed on different levels and the room functions were allocated according to type of occupancy, need of looking out, need for darkness and thermal requirements.

A Zumthor like feature has emerged where Smithsons wanted ‘internal ways’, (corridors to you and me) to have an exposed blockwork finish which had a carefully calculated acoustic quality – ‘the noise of one’s feet getting quieter as one penetrated the building’. This plan was foiled as the university proceeded to plaster these surfaces, which architects described as an occupational hazard.

The plan is attempting to create triangular landscaped courtyards which Smithsons were hoping to be full of mature landscaping after 20 years or so.

The most striking visual feature is the cornice described by Smithsons as ‘ a Moghul style chujja’ which ‘acts like the wide brimmed traditional English ladies’ garden party hat, its wide brim extending a protective field around its wearer yet making the eyes seem larger… it has an effect both of distancing and tempting.’

Smithsons used a similar analogy by calling the timber trelliced work at St Hilda as a kind of ‘yashmack’ offering some protection to the female occupiers of the bedrooms.

While the outer edges of tassels forming the triangular courtyards are straight with ribbon windows and v-joints in concrete surfaces (Smithsons first venture in exposed poured concrete) leading to a language of external surface grooves, the north facing face in between these edges has a zig-zag edge which is firmly held between two stairwell towers rising high to contain air-handling plants at either end.

This orientation of the building is also an attempt to make the back of building look more animated and less of a ‘back’ of ‘centrally focused mat’.

I also feel that Smithsons are referring to Lasdun’s student clusters of East Anglia. This is one of the very few British examples of modern architecture mentioned in their book ‘Without rhetoric- An architectural aesthetic’. They have very cleverly reversed the massing and orientation of Lasdun’s

ziggurats to achieve the architectural shift they sought. I was not able to go in Arts building, or talk to any occupier and therefore am unable to comment about the functional aspects. Unfortunately, the overall appearance of the building, massing and now fairly matured landscaping are not offensive in any way still leaves the architectural anticipations and emotions ‘thirsty’ from such great names.

Non-academic staff building

This building is located on the south side of the main campus in a two storey high detached pavilion. One can see similarities with their famous1960s Upper Lawn Pavilion at Fonthill. The upper floor here looks in three directions and sits on a partly submerged heavily constructed ground floor. I am unable to find out whether this base was some existing structure or created by Smithson themselves. There is a very definite back/service side to this construction but other three sides and indeed the roof have been designed to deter any future additions to the structure. It is meant to be a defined punctuation mark not there to be meddled with in future. All this is perfectly understandable for a building to be seen and used by users approaching this key location from all parts of the campus also ensuring the edges of the ‘mat’ are suitably terminated.

The light weight steel construction of upper floor relies on heavy cross bracings on corner and a substantially heavy concrete fascia beam has been attached to light weight steel sections for support. The recessed voids on semi-sunken lower level remain function-less and are still cause for concern to the university and were recently fenced off.

The concrete fascia may be attempting to relate to the existing vocabulary of older campus buildings but it is worth remembering that the Arts Barn on the other side of the campus has also got a steel roof and fascias both covered with stainless steel skins.

However, the limited availability of funding an inherently expansive and space wasting semi-submerged resting base for a bridged access ‘piano-nobile’ and attached terraces may have produced an adequately functional building, but I am beginning to develop some inferiority complexes about my own ability to appreciate some hidden qualities of these two great architects who possibly are too cerebral for me to follow as I have to admit this building leaves me bereft of any architectural emotions resembling joy or pleasure.

The following issues of AJ were used for References, plans, photos and quotations; AJ 30 November 1983. AJ 16 January 1991.

July 7, 2011 at 10:51 pm

the lower level of the staff building was the first phase. the upper storey and terraces were placed over it 5 or 6 years later. the raised upper level and terraces were for views over the landscape, but as you say it leaves the ground floor as a recessed semi-basement now.

i too struggle with the aesthetics of the smithsons’ later works. they didn’t have an architectural language that was adequate for their intellectual intentions – there are lots of pretty words like ‘chujja’ and an insistence on things being just whatever they are, but the results are clumsy and dull rather than “a poetry of the everyday”. that would have required a certain refinement, an attention to the senses, which the smithsons shied away from. it’s as if they couldn’t actually see their own works.

robin hood gardens is the defining case – a staggeringly ugly building by people who thought they were achieving something sensitive and refined. i’ve been interested in their work since my teens, but reading their justifications i often think “they’re so full of shit”!

July 8, 2011 at 9:22 am

Nice to hear your views and I am certain many architects and people interested in buildings will agree with the gist of your views. However, I wish life was that simple and as black and white as that. There is no doubt that they did their best to avoid designing pretty looking and pleasure-giving buildings and I got to agree that their explanations at times became too pompous for words. However, they are authors of some significant architectural ideas and buildings and in the end their work can only be judged by people in and around their buildings after a decent lapse of time. I hope to pick the thread of these ideas after I finish putting my own thoughts in words for two other buildings on the campus.

May 17, 2014 at 10:30 am

After graduation I worked briefly at the University of Bath’s photographic unit to earn money to go backpacking. Peter Smithson was a regular visitor, bringing table napkins with scribbles which, in a pre-digital age, I put onto 35mm slides for him. I had no idea who he was at the time, being a grubby Physics graduate, though his suits with huge checked patterning and heavy designer spectacle frames instantly marked him out as Someone Who Took Themselves Seriously.

I recall one occasion when he got quite shirty about my inability adequately to represent one of his elongated scribbles within the unalterable aspect ratio of a 35mm slide. If I framed the whole thing, the subtle nuances of it which he so enjoyed were invisible and it looked like a slightly wobbly line. If I zoomed in to select what appeared to me to be the most interesting wiggles, the mastery of the ensemble was lost, in the eyes of the Master when he came to collect the work.

Alas it seemed that even capturing a scribble, the very start of a potential work of cerebral genius, brought this undoubtedly sincere man into conflict with reality.

October 4, 2014 at 11:02 pm

Must have been interesting experience for you. The trait you are pointing out is familiar territory for people who are hoping to carve their names in history books and are aware of the importance of these ‘conceptual sketches’ as references for future historians.

May 23, 2016 at 9:01 am

[…] Acknowledgements: The photograph of the University of Bath Library building, which housed the main UKOLN offices, was taken from a blog post entitled “Smithsons’ buildings for University of Bath“. […]

July 9, 2020 at 1:38 pm

[…] site around 2km from Bath city centre. The Claverton Down campus, masterplanned by RMJM, features five buildings designed by Alison & Peter Smithson, completed between 1978 and […]