The picturesque Cotswold can hardly fail to remind most of us of picture postcards, chocolate boxes and soft schmaltzy classical music but it would be tragic to ignore the vernacular and even worse to turn up the nose at genuine attempt to build modern buildings in these delightful environments.

Edward Cullinan was commissioned to design this residential Study Centre soon after leaving Denys Lasdun’s office and building his own mews house in Camden in 1965.

Edward Cullinan was commissioned to design this residential Study Centre soon after leaving Denys Lasdun’s office and building his own mews house in Camden in 1965.

It may be worth saying a word or two about this generous architect/teacher and now also a Royal Gold Medal winner for 2008, who has influenced hundreds of young architects to carry on the best traditions of a very special ‘romantic pragmatist’ branch of expressionist modern architecture in this country for last half of the 20th century. Calling him ‘collective architectural Dad’ to me is an apt description.

Kenneth Frampton said that Ted produced “.. an architecture of Resistance” and that in his work ” .. both landscape and materiality work together to secure the uniqueness of any prevalent and continuing sense of place”

In my humble view this early project from his office encapsulates the gist of the quotation above.

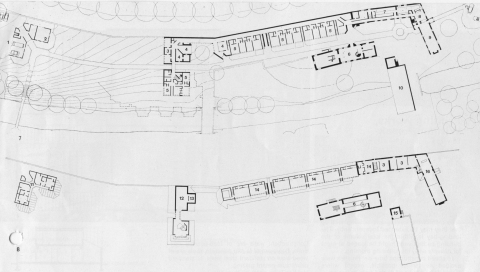

These plans are attributable to Architectural Design, February 1968. It is hoped that the younger architecture enthusiasts could observe that the humble approach to create this subtle and sensitive environment does not use any ‘tight rope tricks’ and yet produces an ageless building which can not fail to enrich all the senses of viewers and users for a long long time to come.

These plans are attributable to Architectural Design, February 1968. It is hoped that the younger architecture enthusiasts could observe that the humble approach to create this subtle and sensitive environment does not use any ‘tight rope tricks’ and yet produces an ageless building which can not fail to enrich all the senses of viewers and users for a long long time to come.

The three buildings in dark lines were the existing structures. The main house was converted to a common room, dining room, kitchen and offices; a malt house is now a library; and the barn now houses the conference rooms.

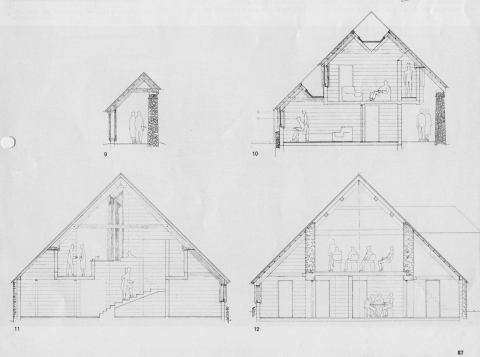

The cross section (left to right) Roof forming cloister round the courtyard; Section through the new main residential block, cloister run next to the boundary wall at the back; Cross section through barn and conference room.

Top left. The old malt house now a library opposite, the old house now connected to the new long housing wing. Bottom right. The footpath passes between the conference rooms on right and new bedrooms on left and leads to the staff houses at the far end of the site. Note the use of insitu concrete and concrete blocks with simple stained timber and stone walls and roofs.

Bottom right. The footpath passes between the conference rooms on right and new bedrooms on left and leads to the staff houses at the far end of the site. Note the use of insitu concrete and concrete blocks with simple stained timber and stone walls and roofs. The new residential wing turns at right angles and reaches the river, enclosing the communal space and separating the staff quarters. The end elevation of this new bedroom block helps to define the river’s edge.

The new residential wing turns at right angles and reaches the river, enclosing the communal space and separating the staff quarters. The end elevation of this new bedroom block helps to define the river’s edge.

Top left. Conference centre with cloister link with residential block; Bottom right. As you leave the village, all you see is the back of the old house and the stone boundary wall forming cloisters behind the residential block. This was my second visit to see the building after about 30 years and I almost missed the building because it was so well merged in its surroundings.

Top left. Conference centre with cloister link with residential block; Bottom right. As you leave the village, all you see is the back of the old house and the stone boundary wall forming cloisters behind the residential block. This was my second visit to see the building after about 30 years and I almost missed the building because it was so well merged in its surroundings.

Stirling, Olivetti and Postmodernism.

January 10, 2010

A lot has been written about James Stirling and his journey from modernism of his ‘red buildings’ to postmodernism of No1 Poultry and since I lived through this rollercoaster period, desperately trying to follow these inexplicable twists and turns, I think time is ripe for me to look back and attempt to discern some hidden logic for this strange journey.

Understanding some of the personal traits of Big Jim, and reading anecdotal tales which abound, attempting to discover any linear development where there is a predetermined slot for all his creative activities would be futile.

There is no doubt that he was a brilliant designer, who always guarded his ‘creativity’ against any attempt to stop him reaching his clear goal of the end product, which he always crafted after thoroughly studying the given brief and context. Any attempt by the clients to change any aspects of presented design was never well received. This I discovered did not happen only after he acquired an international reputation, as Jim was equally hostile to even minor suggested changes on his very first scheme at Ham Common housing in late 50s.

It is said that the staircase leading to Jim’s office were lined with letters of complaint and dismay from clients and users of buildings and displayed proudly as badges of honour giving ample warning to any unsuspecting newcomers.

I am of the opinion that two closely spaced events may well have been the precursor of a major shift in the direction of his creative process; one was buying Thomas Hope’s furniture and second was to employ Leon Krier. These events coincided with the period when he was involved with Olivetti towards the end of 60s and early 70s.

Colin Rowe draws our attention to a perspective drawing (I think that there were at least two) that Leon Krier drew in 1971 for James Stirling’s un-built Olivetti Headquarters at Milton Keynes.

This drawing was meant to be homage by this young draftsman to his master, hinting at his interests in Thomas Hope’s furniture and also history. Stirling sits in his beloved chair, slightly outside the frame of the perspective, with an open book at the table in front, assumed to be a volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre complete. Leon Krier depicts himself as a classical bust looking at the whole scene. Jim is ticking off some young office junior, who, judging by his body language could not care less.

The style of drawing is reminiscent of Le Corbusier and also various other 19th-century neoclassical architects Jim acknowledged being influential for him. Thomas Hope also produced engravings in this style for “Household Furniture” showing neoclassical furniture.

Olivetti Training Centre project came to Stirling on recommendation of Kenzo Tange. I feel that Scarpa and Corbusier’s previous connections with Olivetti would not have gone unnoticed by Jim. Edward Cullinan was asked by Jim to take care of the renovation of the existing Edwardian building and he started to work on the design of the new wing. This was to be his first and the last project where the design is influenced and inspired by clients work. It must be remembered that at that time Olivetti held a place in industrial design world not dissimilar to ‘Apple’ today. Their streamlined colourful injection moulded products were trendy and coveted items.

It is interesting to note that this is one of the few projects from Jim’s office where the building failures and defects of the completed projects have not been brought in the public domain. It is possible that these were not present or it can be assumed that a well-off corporation would quietly take the appropriate steps to resolve any problems as these arose. After all, for them to have a building designed by an international celebrated architect was like a prize business card.

The design of Headquarter building in the new city of Milton Keynes followed the completion of the Training Centre. Unfortunately the computer age had greatly undermined Olivetti’s market position and the HQ was never built.

It is clear that this time Stirling firmly decided to steer away from client product based design and went back to his own familiar way of using various historical and contemporary references to other architects and his own buildings.

Kenneth Frampton suggests ‘evidence can be found of the roof of Leicester but flattened, the tented greenhouse roof of the History Faculty, and the urban galleria and circus hall of Derby City Hall. Outside influences include Aalto’s staircase wall of his Jyvakyla University of 1950, Niemeyer’s organic dance pavilion at Pamphlua in 1948, to Le Corbusier’s Olivetti Computer Centre, projected for 1965. Instead of the singular industrial design references, Stirling is back to his own court.’

Mike Girouard noted that Krier’s … “outline drawing take objects out of space and time into a Platonic world of pure form, undisturbed by accidents of texture or light and shade.”

He thought the impeccable quality of the lines unify the disparate elements represented, helping the viewer to apprehend the underlying qualities that unite a chair by Thomas Hope with Stirling’s design for the Olivetti Headquarters at Milton Keynes.

Was this drawing ‘watershed’ announcing the arrival of “Postmodernism” in Stirling’s work?

PS. A quick look at the time line shows that the work in next ten years or so was; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Sackler, Wissenschaftszentrum, Clore. some of this work can be seen here http://www.flickr.com/groups/675480@N22/

John Andrews Brutalist Megastructure in Toronto

November 27, 2009

One of the best examples of 60’s brutalist monolith structures is a sizeable and well considered building designed for a dramatic site in cold climate. Since a significant slice was built as the first phase by a confident and dedicated architect, the functionality of the building can be assessed to measure various design criteria envisaged by John Andrews.

Unfortunately, the Canadians seem to be shy or ashamed of this significant building and the younger generations of architects seem to be unaware of this example of romantic brutalism, representing a significant branch of modern movement in mid 20th century.

I visited Canada as an architectural student to see Expo 67 and also took this opportunity to see as much architecture on East coast of Canada and USA I could cope on the Greyhound buses. Scarborough College, as it was known then, completely bowled me over. Even my semi-matured architectural understanding could not fail to grasp the ‘magic’ of this building. Luckily the slides I took, survived more than 40 years of storage and a bit of cleaning of digitised images is the basis of my photographs here and on Flickr pages. Set http://www.flickr.com/photos/iqbalaalam/sets/72157603763663802/

Set http://www.flickr.com/photos/iqbalaalam/sets/72157603763663802/

Kenneth Frampton wrote a critique of this building in April 1967 issue of Architectural Design. I am reproducing some of the drawings from this article and paraphrasing or quoting some other relevant parts.

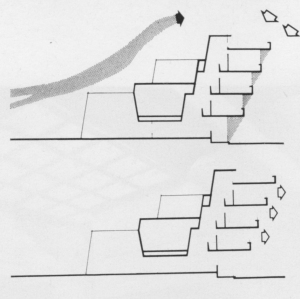

Scarborough was designed as one of the first two satellite campuses to take all their undergraduate programmes. As it was a fair distance away from Toronto, the students were to gain access by car or bus. Kenneth Frampton was surprised to see lack of undercover walks from distant car parking to a building which entirely relied on warm covered student circulation. He assumed that this was either a cost saving measure or possibly certain architectural preconceptions about approach and entry to the building. Andrews wanted the open academic near the admin block to be a dignified, formal hub of the college activity giving access to all college buildings.

The layout is centralized in its organization. The positioning of radiating wings of the building was governed by the site constraints and maximum walking distance of 10 minutes.

“The choice of site has ruthlessly determined the plan profile of the building, making it an obsessive and rock-like extension of the escarpment upon which it rests. The old classic imperative that man-made form be rendered distinct from natural form is at once challenged by this organic parti.”

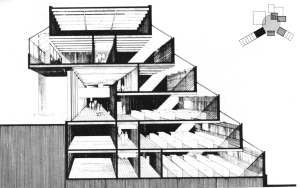

KF considers the building to be a biological organization on an irregular site, difficult to handle formally. Receding or cantilevered wings modulated, when possible, by structural or servicing elements as well as cranked ‘knuckles’ containing lecture halls, changing the direction of wing segments. The entire building is thus ‘coded’ externally to express consistently four different component functions: lecture halls, offices, laboratories and staircases.

The projecting or receding elements also help to form continuous enclosed pedestrian streets rising two floors or full height of the building. The inclined service ducts serving laboratories not only feed and drain waste from the laboratories but also distribute forced air to and from ducts on the roof.

In the humanities wing a two-tiered counterpointed battery of lecture halls maintains a protective windowless wall on northern windswept face, while the faculty offices on south face project out providing solar protection.

In the humanities wing a two-tiered counterpointed battery of lecture halls maintains a protective windowless wall on northern windswept face, while the faculty offices on south face project out providing solar protection.

Tiered sections also provide daylight to internal streets and full height court, ‘meeting place’ placed at the meeting of two converging streets.

“One cannot but be impressed by the ingenuity and generosity of this organization and by its evident operational success. It is a success that is ‘environmentally’ supported by the consistent use of high quality internal finishes and by felicitous light.”

Scarborough possesses a built-in allowance for variable patterns of use…..

As Oscar Newman has observed, ‘The continuous problem of change can to some extent be avoided by the further development of the organic logic and hierarchical organization of spaces and activities—a solution which in itself goes a long way toward limiting the need for large-scale future changes.’

“Scarborough departs radically from the traditional Anglo-Saxon quadrangular university complexes of recent years. It is by far the most daring, comprehensive and radical, and as such merits serious critical attention.”

Towards the end KF writes in some detail about the intellectual aspects of campuses as prototypical city form and compares Scarborough with work of Candilis, Josic and Woods. He considers limits of growth, organization and classic vs. romantic thoughts. I suggest you read the article to read this analysis.

The article ends by stating, “Scarborough belongs to the nexus of thought… shaped by Camillo Sitte ….and travels to Frank Lloyd Wright….. and back in Europe is to be found in the thoughts of an Aalto, a Pietila. It is equally the thought of a James Stirling or a Paul Rudolph. These men are all positively not of the classic mind – and neither is John Andrews.”

After 40 years of expansion and changes, the latest master plan can be seen here http://www.daniels.utoronto.ca/node/753.

When John Andrews was designing and building this in Canada Denys Lasdun was in the middle of constructing University of East Anglia which has many similarities with Scarborough. While Patrick Hodgkinson conceived Brunswick Centre in London almost at the same time as Scarborough was being designed, although it was not completed till 1973. It has a much more urban and slightly formal context as one of the best megastructures of the period in this country.

More photos of this project and other Andrews work on my Flickr set http://www.flickr.com/photos/iqbalaalam/sets/72157603763663802/

For recent photographs see set from Ben http://www.flickr.com/photos/bencnh/sets/72157624082032257/