Archigram to Banksy

February 24, 2013

I bought Archigram magazine as a student in 60s and being an ardent follower, attended as many of their events as I could at that time. Architectural Design used to cover their work regularly and had a big readership among students.

I have been putting occasional scanned images from my Archigrams on Flickr site since 2008 (before the Archival Project existed) and recently a Blog for Archigram Monte Carlo 1969 competition entry published in AD of January 1970. Both my Flickr site and Blog have no commercial slant and simply aim to bring Archigram (and other architectural work of note) as a study resource easily available to the new generations of architectural students and teachers every where in the world, who may know little about the scope of their work and tremendous impact this group made on second half of 20th century.

Having a quick look at the ‘views’ recorded for my Flickr and Blog site for Archigram’s work, I can confidently say that figure is around 50,000. The hits come in clusters and it is not difficult to guess the part of the globe (Papua New Guinea to Peru) where some architectural student class is currently studying some aspect of Archigram’s work by looking at the viewing records against the global time differences

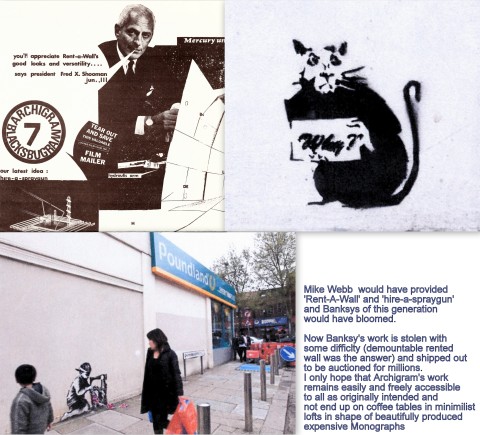

I do ‘smell a rat’ when all of a sudden I am approached by a ‘publisher’ talking about ‘infringements of copyrights’ as I see some kind of profit motive lurking in the background. I know enough about these issues including character and purpose of my web sites at the same time I would hate to do anything to upset either the ‘Archigram Archives’, any original architects or their heirs who are the owners of the copyright. If any of these find any use of the images on my sites offensive, damaging or unacceptable in any way, please write to me as I would withdraw any offensive image or make suitable amendments.

‘Slave Labour’photo by Nigel Howard for London Evening Standard.

Arcives are here: http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/

As promised at the end of February 2013, I welcome the spring by removing all the images from this Blog I uploaded at the end of July 2012. This saddens me but is to conform with the note received from Archigram Archives representative on 22 February 2013 (see below) about the use of copyright materials, a fact which is undeniable. However, my intentions were simply aimed at offering an open learning resource, sharing original Archigram intentions, when I as a student, bought the original magazines for pennies. In todays world these would have been available as a free/open resource for downloading on Internet.

I intend to revisit this Blog in future after studying the background of the competition and looking at some of the social/political changes which were taking place at that time eventually leading to the cancellation of this as a viable project.

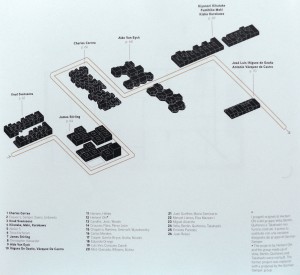

This was a limited competition for an entertainment and sports building on the reclaimed foreshore of Monte Carlo. Archigram reached the final stage and came very close to building in this glamorous city to provide the vibrancy displyed in their graphics.

The Brief required a multi- purpose space to cater for large banquet; variety shows, a circus, Ice rink and cultural activities were also eagerly sought. Architects noticed the lack of a public park and this beach side proposal could extend its services but remained complimentary in atmosphere and experience.

David Greene’s Rockplug/Logplug acted as an inspiration, grassy bank with trees placed over the hole in the ground livened up this depressing area, while offering a glamourous setting as illustrated by liberal use of scanty clad women armed with sun glasses, and a grid of plug-in points for headphones and other modern paraphernalia livening up the site to fit in the famous city of Monte Carlo. All the major functions brief required were housed in a large circular space chosen for its structural properties, covered with a shallow dome hidden under grass, offering extensive supports for all the technoligical kits Archigram could provide to improve upon Cedric Price’s Fun Place and Piano Rogers Beaubourg project.

The aim was to provide a large enough space for banquets, elephants or go-karts; adapting from chamber music to ice hockey. A place where the envelope and architecture was to become subservient to events and the structural systems and services providing magic tricks for multi-use were only playing the ‘second fiddle’.

The buried space was served by six entrances, each show making its own environment, organization and circulation patterns.

Most of the facilities like toilets, normally built-in were designed to be mobile, using a comprehensive set of kit of parts, set at a 6m metre grid and gantries. The aim was to design a place not dissimilar to a live television studio, not unlike ‘Instant City’ in one location. No dividing line between performance and transmitted event (projection, overlay of media). Even after frequent visit to these activities, the visitors may not be able to appreciate the size or configurations within this large cavern.

An architecture that was to be made of the events rather than the envelope as it is likely Archigram considered Beaubourg was.

Peter Cook, Dennis Compton, Colin Fournier, David Greene with Ken Allison, Diana Jowsey, Stuart Lever. Engineered by Frank Whitby.

PS: I am informed that Ron Herron worked on the competition albeit whilst he was in America and consequently on the unbuilt scheme.

The information and original scans are attributed to an article in Architectural Design 1/70 Cosmorama

This building refuses to get out of my mind. I have never been over enthusiastic about classical design, most of work from Christopher Wren and Inigo Jones is appreciated and some of their buildings held in very high esteem. However, this building’s simplicity and the bold form have intrigued me from the day I set my eyes on it the first time in early 60s.

The ‘History of Architecture’ we were taught hardly gave us a clue about details of classical orders or ‘Tuscan Temples’ but recently I sat down to look at some of the history of St Paul’s Church (which proved to be long and complicated) and ‘the pain of it’s birth’ confirmed some of the basic features this building displays to this days. It also defines the genius of an architect who understood the role of significant buildings within the public urban spaces.

The first impression I gain is that the offer of building a new Church by the Earl of Bedford was not dissimilar to the present day ‘planning-gain’ in return for obtaining permission to develop a brand new high quality housing scheme around a new square.

As you would expect the client told the architect to build this ‘gift’ as economically as possible and that famous lines,” … not much better than a barn.” and the reply by Jones, “Well!! Then you shall have the handsomest barn in England.”

Jones also got entangled in church politics by proposing the seating/alter in the opposite orientation to ‘norms’ and wishes of the parish vicar. Jones’s famous ‘Tuscan Temple’ elevation lost a lot of its relevance by becoming the blanked off rear elevation facing the proposed square but his mind was set on gaining a centre piece of a certain stature.

Inigo Jones was at peak of his career and the opportunity to build this prestigious square development was as attractive to an architect then as it is now. This also offered Jones an opportunity to display his unconformity, scholarly primitivism (tempted to use the word ‘brutalism’) and possibly his aspiration to highlight the purity of the early uncorrupted church.

The picture above and below were taken on a cold evening in late February. A time when the stalls are closing and most of the tourists are leaving. Let me show you some sights as seen the same evening.

The office development by Renzo Piano taken from the hotel window. Centre Point is behind Pianos blocks.

The GLC housing almost opposite Covent Garden Tube station in dark bricks looks rather sombre.

The Opera House Development completed by Dixon and Jones in 2000 looks impressive any time of day. The L shaped part of the development making up one corner of the square has carried on with Inigo Jones like colonnade using modern language.

The old vegetable market now houses a busy craft market and expensive shops and restaurants. The basements which were originally vegetable stores have been opened up to become commercial spaces.

Durham Students Union and Arup’s Bridge

December 15, 2011

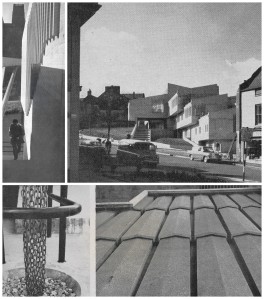

One of the most sensitive and cleverly designed structures of recent times, Kingsgate Bridge by Ove Arup was built in early 60s and was soon joined by a notable neighbouring building, Dunelm House where Ove Arup Associates also acted as structural engineers.

The simplicity and delicacy of the bridge design is seen next to a large but broken concrete ‘jumble’ sitting on a steep slope almost opposite Durham Cathedral. I have been a great admirer of this contrasting ‘duo’ from the day I saw these in mid 60s and my recent second visit has not disappointed me in any way.

The bridge links Dunelm House to other university buildings across the river, while serving various buildings spread around it all over the city. The design exploited the sloping site to its advantage by hiding a large building complex with some large volumes without breaking the existing medieval texture of Durham.

The views from communal and other windows looking over the river and indeed the bridge offer superb views. The reflections of lights and life within the building seen from the opposite bank are also quite exciting.

The building plan is conceived by forming a spine of stair route which collects the visitors at two upper most levels and starts their downward journey on this spine.

All major usable spaces are at various landings along the route. The stair widths and landings reflect the significance of destinations. The stair stops at the lowest level which also houses the largest and less frequently used main gathering space.

The original finishes inside the building were restrained and sombre. The grey concrete and quarry tiled floors were used in most places. The current taste and more affluent student population seeks more Pub/Club like atmosphere.

I am certain that such demands have resulted in use of some bright colours in main stair areas, destroying the unifying and linking function to move between various destinations. The yellowish tinge you see on my photos is result of paint and not the tungsten light or underexposure.

The original white open ceiling white planks with dark sound absorbent filling behind has now become shiny red which one is happy to accept as transient response to cater the tastes of given periods.

The external walls are made of lightweight (foamed slag) concrete fairfaced board marked finish both inside and outside of insulated load bearing external walls. It is remarkable to notice that concrete on Arup’s bridge has suffered heavy staining while Dunelm House is quite free from serious staining. This may be due to some property of the slag and its mix.

The original roof was meant to be covered in Zinc for economy reason, but Royal Fine Art Commission objected and the resulting precast giant concrete tiles were used using a pink shap granite.

This was obviously a step to ensure that the visible roof was part of this cohesive massing and fitted in the townscape more successfully.

The main entrances at the highest point of site at the junction of footpath leading to Arup’s bridge is brilliant design. These entrances bring the users to the head of stairs, feeding them down like a constant ‘waterfall’.

Black & White photos from AJ 15 June 1966 and two other B&W photos and Blue Cross Section from Architectural Review (date not visible) from John Donat’s article.

Black & White photos from AJ 15 June 1966 and two other B&W photos and Blue Cross Section from Architectural Review (date not visible) from John Donat’s article.

Cedric Price, Influential architect and theoritician.

December 5, 2011

Archigram is well known and its influences on architectural world are clearly understood and illustrated. The name of Cedric Price (1934-2003) is often heard in Archigram circles as he was close to the group and took active part in discussions and even contributed but was never a formal member.

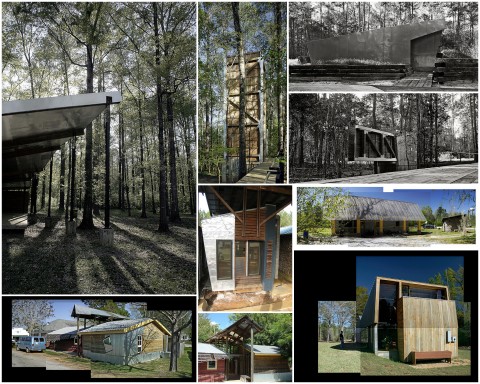

He was born in Potteries his father was an architect who specialised in Art Deco Cinema design. Cedric Price was trained at Cambridge and AA where he also taught influencing many architects, Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, Will Alsop to name a few. He also worked for Maxwell Fry & Denys Lasdun before setting his own practice to build Aviary for London Zoo. He built very little but like many other thinkers had tremendous influence on future direction of architecture which continues to this day.

He was a believer in “calculated uncertainty” where adaptable, temporary structures were preferred. He believed that an ‘anticipatory architect’ should give people the freedom to control to shape their own environments. All buildings according to him should allow for obsolescence and complete change of use. Will Alsop, who worked for him in early 70s recalls CP’s delight in designing a Cafe for Blackpool Zoo which was eventually to be turned into a giraffe home. This fitted perfectly into his themes of uncertainty, adaptability and change.

In his ‘Thinkbelt’ University project he proposed simple, moveable buildings which would deliver education “with the same lack of peculiarity as the supply of drinking water.”

His most influential project was ‘Fun Palace (1961) ‘ for Joan Littlewood. It was killed off by local government bureaucracy. The design of Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s Pompidou Centre in Paris is called a direct descendant. Soon after that he designed ‘ Potteries Thinkbelt (1964)’ which still makes great deal of sense. Among his built projects only Aviary in London Zoo remains, as he ensured that the other temporary structure for a community use ‘Inter-Action Centre’ in Kentish Town was not listed but demolished as intended. It is also amusing to recall that he was the only architect who was a fully paid-up member of ‘Britain’s National Institute of Demolition Contractors’.

“Aviary was designed for a community of birds and his idea was that once the community was

established it would be possible to remove the netting . The skin was a temporary feature: it only needed to be there long enough for the birds to begin to feel at home and after that they would not leave anyway. ………Price the theoritician, functionalist was frightened of and avoided style. …. he wasn’t interested in being remebered. He was building a memory.” 1*

Later in his life he worked on ‘Magnet City’ which was an exercise in using intermediary spaces in London urban landscape to stimulate new patterns and situations for urban movement in the city. shown in an exhibition in 1997.

He also contributed to the ‘Non-Plan’ debate with Paul Baker and Peter Hall. This basically was an ‘anti-planning polemic’ which resulted in the formation of ‘enterprise zones’ like Canary Wharf in London and ‘Metroland’ in Gateshead. On personal level I never came to see great sense in this reaction against the previous planning failures and put in their this ‘free for all’ American style money making system even if it generated big business and attracted lots of users.

1* Will Alsop’s recollections.

Photo above shows three views (interior & exterior) of Fun Palace by Cedric Price 1962.

Smithsons’ buildings for University of Bath II

July 10, 2011

The School of Architecture and Building Engineering (E6)

What is ‘Conglomerate ordering”

To understand the most significant building by Smithsons on the campus, the school of Architecture and Building Engineering or E6, one must try to comprehend the ideas behind ‘Conglomerate ordering’ which emerged in Sienna period of ILAUD.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilaud This building demonstrates many of these ideas and twenty years of use have also thrown some light on Smithsons hopes and expectations.

Following summary is abstracted from AJ 30 November 1988

1CO.* ‘ A building of conglomerate ordering is hard to retain in mind… it is elusive except when one is actually there; then it is perfectly lucid.

2CO. ‘It brings all our senses into play through the widest possible differences: fear and pleasure mixed together.

3CO. ‘The building has a thick building-mass; (as La Granccia di Cuna and Santa Maria della Scala) not very high…penetrated from the top for light and air.

4CO. ‘The roof of a building is another face …all faces are of equal value, all equally considered, but non are “elevations”.

5CO. Conglomerate buildings are an inextricable part of larger fabric .It has no back, no front; it is equally engaged with all it confronts. A change within its “convention of use” enhances its sense of order.

6CO. Its fabric can accept interventions.

7CO. It is dominated by one material… the conglomerate’s matrix.

8CO. It seems to be pulled-down to meet the ground, not the ground built-up to meet the building.

9CO. It is lumpish in weight and has weight.

10CO. Its bearing walls and columns diminish in thickness as their load or need for mass diminishes; walls and column spacing is irregular, responding to use and natural placing.

11CO. It has a variable density plan and a variable density section.

*The numerical referencing above does not represent any order of importance and simply being used to refer to my descriptions/observations regarding this building.

E6

I consider the location and design of this entrance building as pivotal for the campus. Not only it was to act as a ‘sign post’ for entrance but it was to perform the task of moving thousand of students and staff from ground level to main raised deck and down again. It was built well after completion of 60’s campus development, indeed almost at the end of the productive life of the architects, who were also going to show their final hand to test and explain ‘Conglomerate ordering’ among other thoughts.

The best way to share my views of this long awaited visit is to understand and explain architects intentions and then try to share the buildings in their present context. The wear and tear caused by the general use and age and any changes due to change of functions can then be highlighted. I am afraid some effort is required on our part to understand the architectural process used by Smithsons which produced a small body of disparate work of undisputed architectural significance.

Let us start by describing the impact of arriving at the campus for a first time visitor who has just parked the car in nearby visitors’ car park. The positioning of a large bus stop/vehicle turning place with bus shelters around it and pedestrian friendly surfaces, surrounding landscaping and buildings announce that this is more than a bus stop and makes you register it almost like a town square.

This feeling of arrival is reinforced by the presence of a slightly odd end of a longish slab building which is welded to this ‘arrival space’ near one edge at a slight angle as though it is trying to envelope the ‘space’ just described.

Since you have no clue as how to enter this huge complex of buildings, your eyes run past the end of the ‘odd’ building and there is no doubt in your mind that a major route is being announced by presence of very wide steps attached to this building looking straight at you. This invitation (with an Italian accent) is irresistible and without any hesitation you undertake this journey of discovery.

Oscar Niemeyer’s sketch from his 2003 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion is for me the best analogy I can offer (with the sincerest apologies to Smithsons but possibly delight of Neiymer). Can you imagine asking some student at the bus stop for directions to get to Architects Department and getting a reply “Go up to the knee and turn left, but don’t take the lower path” or “Library? ah! go right up to the belly button and turn right”.

The wide steps are arranged some distance apart at different angles hugging the side of the long building. You notice the steps reduce in width as you climb and you also gradually find yourself under the cover of upper construction of this building. You are also aware of obstacles like balustrades and local ramps near doors trying to impede your upward journey.

If you happen to look into the building through the windows on left, you are bound to notice large display of architectural photographs fixed to a corridor wall running parallel to the route you are following. Some entrance doors to this corridor and signs indicate that these doors take you to the School of Architecture. If you look to your right and backwards you would have gained enough height to see distant campus building and the country side.

After a fairly long walk but gentle ascent, these steps bring you to a very large platform on the right. This space has trees and is surrounded by lots of high building on each side and bridging overhead. The ‘odd’ concrete building with attached steps which offered cover to this route has now attached itself to one of the older arcaded buildings around this raised area, and you are still walking in an older arcade.

(The width of Smithson steps was predetermined by an existing arcade of the same width to which these originally connected to, well before the upper deck was reached. This in not the case any more, as the deck has been extended towards E6 to meet it and a new lift has been located here basically to for disabled users. This act of arrival via steps of fairly restricted width to a very wide platform originally was a puzzle to me as there was no apparent reason for not finding a more generous stepped ramped approach. Another set of stairs has been added to the other side of the road as well (second of Oscar Niemeyer’s sketch legs).

Having reached your destination, like any sensible architect, you retrace you steps and experience the journey backwards and explore the other side of this ‘oddity’ of a building. This is an entirely different world. A great deal of raw building materials and machinery paraphernalia dominates the back yard; you obviously are in the Building Engineering department of the campus. This area has its own vehicular access and much more formalized disposition of windows responding to other surrounding buildings. There is also a bit of playing with forms (God forbid!) as the back of lecture theatre shows its presence by two chamfered walls expressed on external elevation.

When you see the end of the building facing the ‘square’ carefully, it becomes apparent that this also acts as a cross section explaining the assembly of the constituent parts (corridors, roof lights, Workshops supporting studios, roof platform for daylight studies for school of architecture).

There are two doors linking School of Architecture to the grand staircase at slightly different levels and in turn connected with another local circulation passage running parallel to the main stepped route offering views in and out and also offering on display some architectural activities and serving a generous crit room also acting as a lecture space. Two stairs and a lift also connects the entrance level to serve most of studios, seminar and workrooms on two floors above and access to the ground level below.

A walk in the school of architecture soon reveals that there is a great shortage of social and informal meeting spaces throughout the building. The circulation spaces are too restricted to offer any other meaningful activity. I assume it is a direct result of financial straitjacket architects found themselves in dealing all the work on this campus.

A quick look at the list of ‘conglomerate ordering’ (with numerical references above) reveals that Smithsons have managed to achieve most of their aims.

1CO- I can verify that building is hard to retain in mind as despite my best efforts to recall what I saw internally, I was unable to draw a plan with any certainty.

2CO- matter of all senses I am afraid is difficult to comment on. Fear and pleasure are strong words. The daylight quality in studios and views are pleasurable and nice.

3CO- Building has thick mass and lit from the top indeed.

4CO- All faces, including the roof are well considered and are of equal value.

5CO- The building equally engaged with all it confronts. Some major changes within the building have already successfully taken place without any change to sense of order.

6CO- Fabric is continuing to receive interventions and thriving. For examples most of the studios are new interconnected with new openings and various walls have been added or altered.

7CO- The use of Bath stone and concrete frame remains the conglomerate’s matrix and weathering well. Horizontal banding of concrete is even more pronounced because of lichen growth on it.

8CO-The grand staircase literally pulls the building to ground. The walk on grand staircase offers interesting little incidents but does not make any attempts to perform visual gymnastics which have become the hallmark of new generation of architects. The real contribution lies in linking one newly created space to an existing one, without trying to dominate any but keeping the interests alive throughout this transition of height.

9CO-Building is lumpish and has weight.

10CO-Walls and columns respond to load and reduce where possible. Columns are irregularly placed for many areas responding to use.

11CO- It has a variable density plan and section.

When the building opened all of the School of Architecture could not be accommodated here but now it is all under this stainless steel roof and looks very happily settled as one can gather from the usual assuring clutter of models drawings and odd furniture in well lived in studios.

The exposed services originally were considered crude but constant changes have proved that this was the right decision. The building must have absorbed many changes to services particularly in relation to new IT changing needs. It appears that the results are more than satisfactory and continue the original relaxed looking distribution without any known failure of crops of young architects coming out of this school with phobias about exposed services. I have no doubt that this building would remain a fitting tribute to the architects who chose to close their architectural account with this. It may take some time but I am sure it will mature like a good wine.

All old B&W photos, plans and various absracts taken from AJ of 30November1988.