Looking back.

July 20, 2020

Covid virus pendemic, old age catching up with you and ever reducing list of your old friends and colleagues superimposed on resulting isolation, and social distancing is enough to make you fondly reappraise your past interests and activities trying to gauge the past efforts and the current dirth of continuation of these old obsessions.

Having looked at pages of this blog for last 10 to 11 years proved to be quite a sobering experience. I will go as far as saying that I was surprised to note the amount of effort and time I managed to plough in gathering these thoughts and information together in one place without any major complaint from my late partner.

Although the temptation to continue these efforts as before is still there and inviting you to particpate is attractive but the reality and lessons learnt over last decade or two are simply shouting “Don’t be stupid – just have another nap and you will regain sanity”.

I feel there is a compromise in sight. If my fading grey matter and slower body permits, a system of short re-visits (if the buildings survive) and the impact of raveges of time on them may be worth recording with some continuity seen from the same pair of eyes after many years but filtered through layers of coloured curtains of changing times.

I also feel that I may be able to impart some pain on the visitors to my Blog by forcing them to look at some of my own meagre architectural efforts as an architectural student, trainee and finally as a practicing architect in various Public Authorities after completely bypassing the private architectural practices I could have chosen to work for.

Let me start with my own neighbourhood. The Market Square and Church form the heart of old Winslow and almost all buildings in this area were brought in line with the prevailng fashions in 18th and 19th century to give the central Winslow a suitable appearance to represent a prosperous central town serving this rural end of Buckinghamshire. Here you see the two white painted properties facing the High Street. If you walk through a black door next to the shop window leading to a narrow alleway and look back towards the rear elevations of these two buildings this is what you would see.

The odd collection of buildings from 14th to 18th century using differing materials and constructional methods have been ‘brought up to date’ to offer a unfied veneer facing the High Street conforming with the prevailing tastes.

This kind of renewal still happens all over the world but under modern names not unlike ‘post-modernism’.

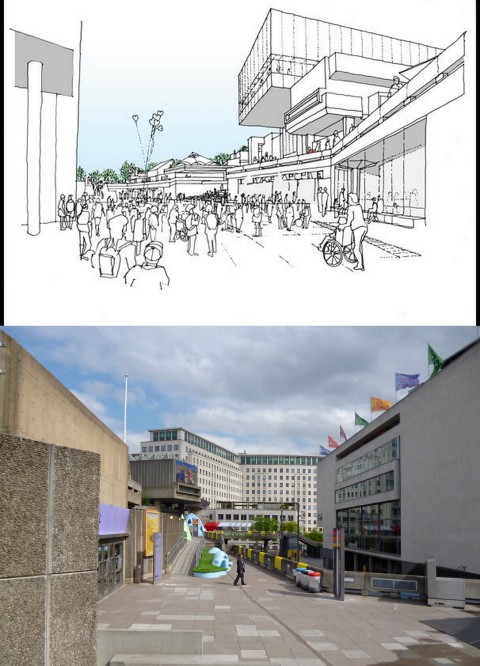

Latest South Bank Redevelopment Plans, London

June 18, 2013

South Bank Redevelopment Proposals by Fielden Clegg Bradley Studios.

( 4th July 2013. After some serious criticisms from National Theatre, the client/architects has agreed to withdraw the current planning application to carry out further work before resubmitting it. Sensible move for all concerned and us.)

You may have gathered from my recent contributions on Flickr that I have virtually grown with the South Bank and have been a frequent user of all the venues in this area from early 60s to now.

I have also admired Fielden Clegg Bradley Studios work for some time. With this background, I would like to express some of my initial views concerning the proposals which are based on fairly sketchy information released to the press.

I was of the view that this complex should not be listed, however appointment of an intelligent architectural practice and a sensible brief was essential to do justice to the site and it was a relief to see FCB appointed.

It is obvious that the client is desperate to cram maximum accommodation on this site to meet their expectations after leading a frustrated existence without having many ‘bells and whistles’ similar recently built projects have in major cities.

Architects seem to be performing a difficult ‘tight-rope’ trick and their initial offerings seem quite an outstanding achievement. This is not a bad time to raise concerns by observers who know this area and its history of growth and have some constructive criticism to offer.

The architectural pedigrees of the original 60s buildings and RFH are well known and ‘over-reverential’ architectural approach to alterations sometime expected by conservationists would be inappropriate in this instance.

The proposals for central raised block facing RFH may appear large but I see this as a good location to gain badly needed accommodation.

My only observation (not a criticism) is that the existing pedestrian route under Waterloo Bridge connecting this main space to the terraces of National Theatre is extremely restricted and arrival at the side of NT from under the bridge is a disappointing experience and is a bit of an anti climax. Some improvements around here, with blessings of NT, would be hugely beneficial to all concerned.

My main concerns relate to the long glass block running parallel to the bridge housing Poetry Library, Literature Centre and Restaurants.

The building works and fits well when seen from Hungerford Bridge side as it acts as another ‘book-end’ (the other one being the new building between RFH and railway track) and neatly contains the activities on this side of the Waterloo Bridge.

However, in my opinion all the negative factors come into play from Waterloo Bridge and NT side. Let me share some of these negative aspects and its impact on the surrounding area.

- The pedestrians and drivers when crossing the bridge are able to see concrete structures of NT on one and QEH, Hayward on the other side with their distinct ‘idiosyncratic approaches’ almost having a dialogue with each other.

This would be interrupted by the new block at least at QEH end.

- The end elevation of this block as seen by people on the bridge approaching Waterloo Station would be out of character and far from satisfactory in its scale and appearance. Although the views from inside this building can be very exciting.

- The views from the roof terraces of National Theatre currently enjoying the side elevations of QEH would be lost for ever depriving the witty bouncing of a concrete banter between these dissimilar but contemporary icons.

- Walking at the bottom of a fairly long sheer wall of this block close to the Bridge pavement is alien in to the local urban context. A similar situation is only experienced where the pavement abuts the building line in Lancaster Place which directly relates to context of Strand and well before the bridge starts. Once you are on the bridge the ability to look down from pavements on both sides exists throughout the length of the bridge which will be disrupted by this block.

An important architectural location without listed status puts even more onerous responsibility on a caring and gifted architect and the client. This is a good scheme to prove that excellent results are possible to obtain without ‘crutches’ of listing status.

The end of the linear block would rise on the left of QEH. Lower floor is probably Cafe or Restaurant.

The views from the footpaths of Waterloo Bridge give you glimpses of a busy riverside walk and various terraces of NT.

All sketches and perspectives from Architects press release and photos by Iqbal Aalam.

More photographs of this and other GLC projects see

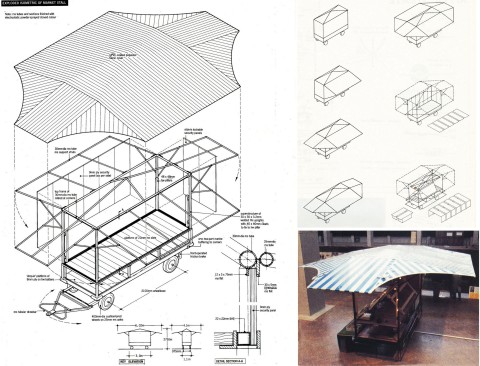

Cedric Price’s Market Stall. Proto-type

March 27, 2013

Markets with ‘temporary’ stalls are common sight in most of the country. Some Market Squares which open frequently have now fairly rigid and semi-permanent structures to provide shelter to stalls and often the customers. The traditional wheel barrows with a light weight roof can still be seen where opening hours are limited and a swift removal to clear the streets is essential, but this mostly applies to fruit and vegetable like produce.

There are more and more specialist stalls serving a variety of food, electronic goods and even Barber shops. The frequent rain inevitably creates water pools in fabric roof and canopy structures and the sight of stall holders trying to use poles to push the water puddles often create sudden water falls on or near customers who are used to weave their way as seasoned market users.

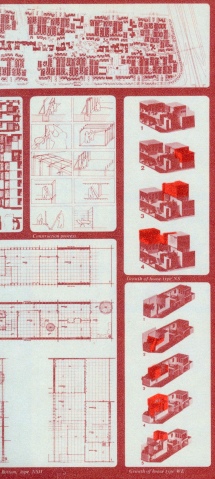

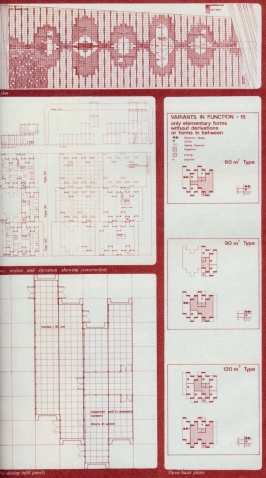

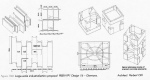

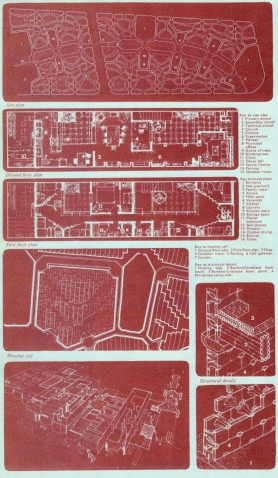

I do not know who came up with the idea in Westminster City Council to ask Cedric Price to improve the streetscape and propose design for a flexible market stall in 1987, but it was a brilliant move. This is the kind of project Cedric Price would have welcomed as a real challenge as the end product had to be light-weight, secure, moveable and able to offer a flexible multi-functional combinations of use as well as offering shelter to the owners and the public being served.

Price came up with a steel framed hinged box on a wheeled structure which was self bracing in any position. The stall offered generous canopies on all four sides and were capable of operating in different combinations and linking with other stall canopies, to offer naturally ventilated covered walking and shopping areas. The taut canopies stopped flapping noises and avoided formation of water pools above walking and serving areas.

The ply panels were fixed to side of steel frame forming a back to the PVC polyester coated fabric in closed position and were also used for counter-tops.

The stalls were able to be folded down locked up and towed away quickly and easily.

Apart from the proto-type shown in AJ it is not known if more of these stalls were ever built and used.

Information and stall photos attributed to an article by Susan Dawson published in AJ 5th September 1996.

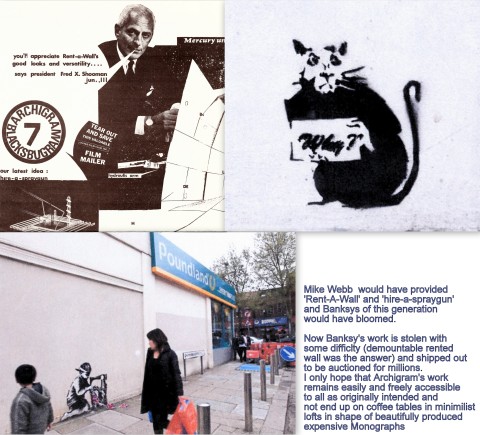

Archigram to Banksy

February 24, 2013

I bought Archigram magazine as a student in 60s and being an ardent follower, attended as many of their events as I could at that time. Architectural Design used to cover their work regularly and had a big readership among students.

I have been putting occasional scanned images from my Archigrams on Flickr site since 2008 (before the Archival Project existed) and recently a Blog for Archigram Monte Carlo 1969 competition entry published in AD of January 1970. Both my Flickr site and Blog have no commercial slant and simply aim to bring Archigram (and other architectural work of note) as a study resource easily available to the new generations of architectural students and teachers every where in the world, who may know little about the scope of their work and tremendous impact this group made on second half of 20th century.

Having a quick look at the ‘views’ recorded for my Flickr and Blog site for Archigram’s work, I can confidently say that figure is around 50,000. The hits come in clusters and it is not difficult to guess the part of the globe (Papua New Guinea to Peru) where some architectural student class is currently studying some aspect of Archigram’s work by looking at the viewing records against the global time differences

I do ‘smell a rat’ when all of a sudden I am approached by a ‘publisher’ talking about ‘infringements of copyrights’ as I see some kind of profit motive lurking in the background. I know enough about these issues including character and purpose of my web sites at the same time I would hate to do anything to upset either the ‘Archigram Archives’, any original architects or their heirs who are the owners of the copyright. If any of these find any use of the images on my sites offensive, damaging or unacceptable in any way, please write to me as I would withdraw any offensive image or make suitable amendments.

‘Slave Labour’photo by Nigel Howard for London Evening Standard.

Arcives are here: http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/

Crematorium, Crownhill, Milton Keynes. An homage to Louis Kahn.

February 11, 2013

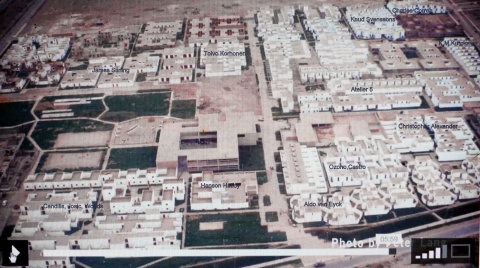

The high quality of architectural and planning output during inception, birth and infancy of Milton Keynes was not accidental. Derek Walker led a gifted team of professionals working with him in MK Development Corporation and commissioned good architects of international and national repute to build housing, civic and other building types within the city.

The demise of MKDC in 1992 and subsequent political changes started to dismantle the architectural department within the Council which was supposed to take over and supervise the responsibility of completing the growth of the city.

The financial constraints and changes in house building/selling sector started a race to build to obtain biggest profits and financial savings without much regard for sensible commissioning in order to obtain the best possible architectural quality to fulfil the original goals of design and planning.

The decline in architectural standards is so overwhelming that the earlier levels of ‘acceptable/mediocre’ can now easily pass as ‘excellent’ and if anything of some merit is built, it is welcomed with disbelief and needs celebrating.

The building of Crownhill Crematorium is such an example where a series of happy coincidences led to ‘birth’ of a building dealing with the emotional issues of ‘death’.

The so called birth took place in the back seat of a taxi (assisted by the father) as it was rushing to reach hospital.

Adrian Morrow, the young project designer with an impressive list of buildings to show against his name and a long list of first class architectural practices he has worked for, happened to be working in Architects Department during its death throes when this project arrived on his desk. The rapid population growth of the city meant that the existing crematorium built in 1982 by Roger Hobbs was unable to cope with the increased demands.

Adrian Morrow’s commitment to good architecture must have speeded his efforts to complete work on Crematorium detailed design, fighting against uncertainty of existence as Council’s architect. The new energy regulations and sustainability issues were dealt with and working drawing stage completed speedily before the inevitable ‘Project Managers’ took over the job and Council’s Architecture Department’s ‘life support’ was withdrawn and unwittingly the department became the first candidate for cremation in the new building (metaphorically speaking of course, just like Asplund’s in Woodland Cemetery).

The opportunity of seeing a worthwhile building in Milton Keynes after a while is too good to miss. It may not be able to withstand a direct comparison with Asplund-Lewerentz’s Woodland Cemetery in its scale, masterly handling of landscape and classicism of Swedish vernacular but there were lessons to be learnt.

The comparison with the other famous example of Funerary buildings, Scarpa’s Brion Family Cemetery (1968-78) would be grossly unfair at various levels but relevant when considering the experience of family and friends during emotionally traumatic occasions when the intimate internal and external spaces are able to offer solace and contemplation to affected users.

However, since the architect fairly and openly acknowledges Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum as the main inspiration for this building, a few related things are worth discussing.

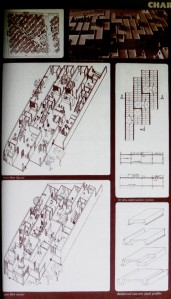

Like most architects of his age, Adrian Morrow knows and understands Kahn’s work, (as Charles Correa’s use of Kahn’s Trenton Bath House at Gandhi Ashram in India) chose to use Kimbell’s vocabulary of concrete vaults with flat roofs to create ‘servant and served’ spaces. A good model to follow, as judicial spacing of vaulted roofs proved flexible to cope with varying and sensitive space requirements of the brief for internal and external spaces.

The roof was originally designed before the sustainability requirements imposed rows of wind catchers. These clusters distract the eye from the simplicity of extruded vaults used by Kahn, but since the intentions are noble and a touch of ‘science fiction’ adds an extra layer of experience, I find it more than acceptable.

My main disappointment lies with the way the car park sits in front of the building dominating the approach and exit for the mourners. The act of approaching the imposing entrance vault through cars looks abrupt and cluttered. Similarly the car park dominates the view as you leave the chapel using the side exit via an intimate well designed landscaped courtyard, created by parting of two vaulted roofs. The marrying of cars building and landscaped/water side walk is unresolved and to a degree lets the project down.

The experience of washing your hands using the warm water in the toilets attached to the entrance vault on a cold morning was even more satisfying knowing that the source of heat for this water was provided by recent departed ‘user clients’. You can’t but say “Thank you and Thank you God for effective recycling….”

Adrian Morrows web site with a video:

http://www.ajmarchitecture.com/envprojectajm.html

An excellent video showing Scarpa’s Brion Family Cemetry;

http://architechnophilia.blogspot.co.uk/2011/12/carlo-scarpa-brion-tomb.html

Cedric Price, Anticipating the unexpected, Magnets.

October 29, 2012

Towards the end of 1996 Cedric Price explored seven projects on the theme of anticipatory architecture, which were published in Architects’ Journal of 5th September 1996. This publication was followed by an exhibition called ‘Magnet’, arranged by The Architecture Foundation held in London from 18th April to 8th June 1997.

There is hardly any point in writing anything as an explanation or summary for Cedric Price, a difficult enough task for expert architectural writers, but in my inadequate hands it will be nothing short of a disaster. My thank to AJ and Kester Rattenbury for borrowing the abstracts from their writings.