Introduction to Architectural competition, Brief and building of samples of entries focused on James Stirling’s proposals. 1965 to present.

“PREVI, Spanish initials for “experimental housing project”, was conceived in Lima in mid 60s. In 1965 Peru’s Architect president Fernando Belaunde Terry began consultations to explore the ways of controlling the flow of people seeking urban living and spread of self-build informal barriadas in urban Peru. The proposals were submitted to UNDP in 1966 and approved in 1967. The work started in 1968 with the intentions of carrying out three pilot schemes over three years.

Three original winning schemes could not be built in accordance with earlier intended scale or details. In the end jury decided that the best way forward was to build all 26 submitted proposals because of their high quality. Most of the competition invitation work and implementation of building of 24 out of 26 schemes was masterminded and overseen by the British Architect Peter Land.

The forty years that have lapsed in the interim and the ongoing transformation of the homes by their dwellers afford an opportunity to reflect on the suitability of the construction technologies proposed in the competition. Ongoing growth and the rationalization of construction methods were two of the basic premises underlying the competition. The remodeling that has taken place in the interim stands as proof of the success of the first premise, but the use of traditional techniques to build the additions calls some of the most sophisticated proposals for industrialization into question. At the time, the tendency was to rely on large-scale industrialization, as can be seen in the German, British and Polish architects’ proposals. Nonetheless, many of the PREVI proposals opted for rationalizing construction and precasting short series of small elements, rather than huge three-dimensional members. In the situation presently prevailing in Latin America, the viability of some of the technological proposals deployed in the PREVI might be profitably revisited.”

Abstracted from a paper by : Julián Salas and Patricia Lucas (Italics additions by self)

The process of building in PREVI was originally intended for large scale provision of housing, which was to create a transformable core model with one room and provide basic utilities for the unit. The idea was that the new owners were free and encouraged to expand in accordance with the needs of their growing families and their own financial situation. In these new projects the hope was that rather then using salvageable and recycled materials suitable and dependable construction would be used and paid for by the owner/occupants. This process allowed the owners tenants to control their own social, family and cultural needs making them more involved and motivated towards the project. It was also hoped that the ideas generated by the competition would introduce new methods of creating energy efficient, seismic resistant and cost effective building techniques.

The architects and project managers under the lead of Peter Land took a holistic approach in building the fruits of this rare International competition for social housing.

“If Weissenhof Siedlung is the natural childbirth of social housing in the First World, PREVI is the coitus interruptus of Third World housing”

I sincerely hope that success of this project (although far from pretty in comparison with seductively dressed social housing schemes on offer in better-off countries) hidden in a remote part of world will offer useful lessons of construction and design to professionals and students with strong social conscience. The lessons should be absorbed and filtered down to educational curricula throughout the globe to inspire future generations of architects in solving the international housing dilemma facing millions throughout the world.

General notes.

The Government of Peru formulated an experimental project in housing which had an objective of developing new concepts of forming experimental neighbourhoods and techniques utilizing Peruvian and foreign experience. In 1965 its Architect president Fernando Belaunde Terry began consultations to explore the ways of controlling the flow of people seeking urban living and spread of self-build informal barriadas in urban Peru. The proposals were submitted to UNDP in 1966 and approved in1967. The work started in 1968 with the intentions of carrying out three pilot schemes over three years.

In PREVI, 13 internationally renowned architects were commissioned to develop prototypes of urban housing that would internalise programmes for any future transformation. Thus each unit contained the terms of its own growth, recognition of the value of the dynamic of growth adopted in the informal slums. In contrast to a growth model based on large, out of scale gestures – from megastructures to gigantic superblocks – the PREVI experiment fielded new dynamics based on a model of low-rise, high- density housing.

When in 1968 a military coup led to the overthrow of the president-architect who had promoted the PREVI project, the involvement of UN prevented the project’s cancellation.

The jury met in 1969 and having chosen 3 winning projects from 13 International architects ( Kikutake-Kurokawa-Maki 4; Atelier 5 and Herbert Ohl), resolved to initiate the construction of all but two of the proposals in 1974, the first phase of 500 units was finally built and left to its fate of growth and progressive oblivion.

The 13 invited International architects were; Toivo Korhonan 6; Charles Correa 1; Christopher Alexander 8; Iniguez de Ozono & Vazquez de Castro 10; Georges Candilis; Alexis Josic; Shandrach Woods 13; James Stirling 7 ; Esquerra & Samper 2; Aldo van Eyck 9; Kikutake, Kurokawa & Maki 4; Svenssons 3; Hanson & Hatloy 11; Herbert Ohl 12; Atelier 5 5. (Jose Antonio Coderch from Spain was one of the Jury members)

The numbers after the name refer to general layout marked with numbers. The brown areas on the layout indicate subsequent additions extending the original built forms.

Summary of the brief.

Mandatory requirements were that each dwelling plot was to be between 80-150 m2, of which dwelling was to occupy between 60-120 including all floors.

The buildings initially were to be 1 or 2 storeys designed to support the third floor and were to be based on100 mm module. The ideas were to explore and develop techniques in architecture and construction within general area of low rise, fairly high density and compact housing in terraced, row and other formation. High rise developments were ruled out.

Detailed designs of dwellings were to be submitted with only a schematic general design for the community. All dwellings were to be flexibly planned for eventual accommodation of eight children of different ages, and one elderly couple, in addition to the owners.

Each dwelling had to provide living, dining, kitchen, bedroom(s), bathroom(s) and service patio. The relationships between rooms and external spaces were defined. Roof areas were required to be suitable for outdoor space.

The dwellings were to be conceived not as a fixed unit but as a structure with a cycle of evolution with appropriate construction technology to achieve this aim.

The initial basic unit was to be built by the main contractors and technical advice and assistance in building will be made to families completing their houses.

Car parking spaces were required to be on individual plots although at this time most of the families did not own cars.

James Stirling’s Proposals.

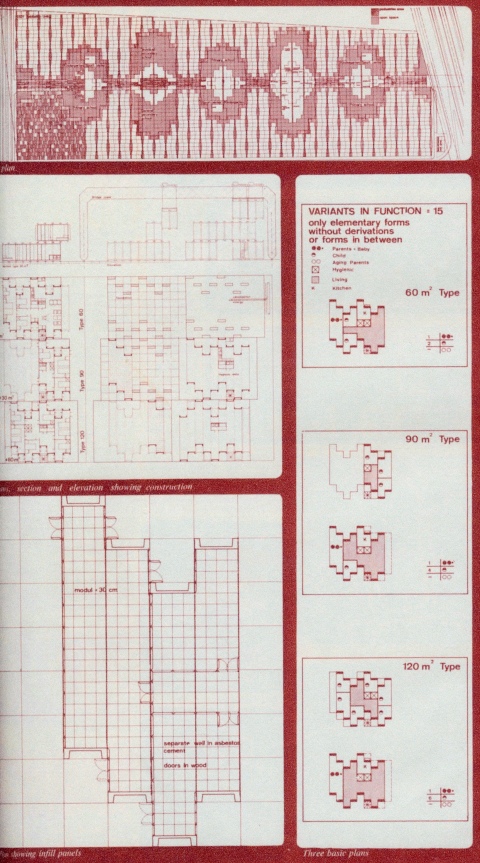

After the ‘first build’ by the contractors it was intended that the house should be completed at ground level and above by house owners in self-building styles.

The growth plan drawing shows in stages of self-building a 4P house becoming a completed ‘one storey house’ (8P+) considered the most typical method of growth. Thereafter expansion takes place on the floor above, either as a separate dwelling or, in the case of a large family, as additional bedrooms and living spaces, in which instance part of the ground level accommodation could be used for other purposes (i.e. shop or garage etc.).

When the house was at its smallest (4P), the kitchen, dining and living area were shown combined. As the house increased in size to approximately 6P the dining and living areas were separated from the kitchen by a wall and doors. This wall (knock-down or moveable) appeared in a new position when the house becomes 8P and 8P+, increasing the living space of the house as the family size grows.

Each house had two front entrance doors. One door led directly into the living area (social/traditional), the second (functional) into the house circulation area leading via the staircase and garden patio through to the service patio.

All rooms were planned with through ventilation i.e. separate openings on opposed walls to create cross draughts.

The ‘first-build’ by the contractor takes advantage of the large-scale initial production (cost and speed of erection) and was an assemblage of precast concrete walls and floor units. Party walls and outside perimeter walls were of sandwich construction and were precast units rising from ground beams incorporating windows and door openings and also parapets – these were crane erected.

Roof/floor units were lightweight r.c.beams with hollow pot infill which could be man erected allowing self-help methods of construction t as expansion was required.

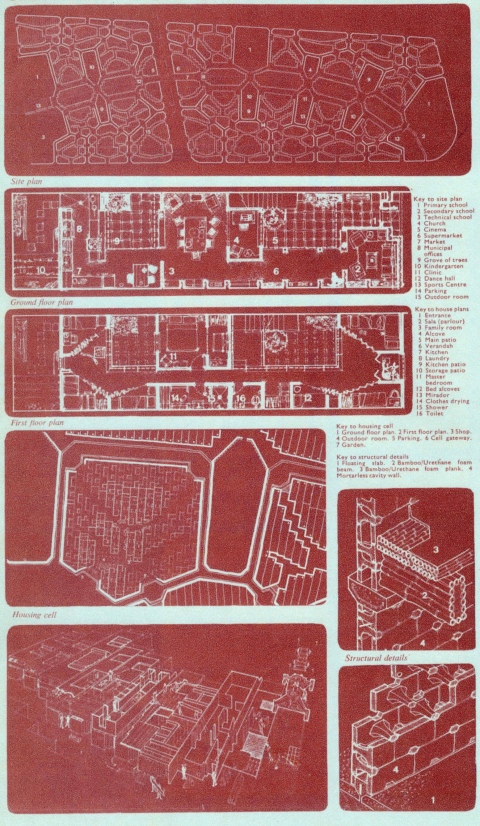

Just as the individual rooms of the house were grouped around the garden patio, similarly the various sizes of house groupings were linked with differing scales of social and community space.

The hierarchy grew from the individual house to the immediate neighbours by making an initial group of four houses above common party walls (and common services) grouped around the service patios. These clusters of four house units were then grouped around a common entrance patio forming 20 or 21 houses. Thereafter this larger group becomes the basic cluster unit forming the neighbourhood (approximately 400 houses) and was related to access roads and car parking. There are four such neighbourhoods the allocated site area (1500 houses) and each is separated by a Public Park (planted, informal garden valleys) in which were to be sited the schools etc.

Flanking the approaches to the neighbourhood parks and enclosing the end of the housing areas were reserved for commercial buildings, shopping and community centres.

Stirling in 60s.

James Stirling was well informed as far as CIAM and its views on housing were concerned. He had already carried worked on proposals for a village scheme using vernacular and simple construction. At this time Europe was swamped with large concrete panel housing construction showing off their economy due to scale and rapid construction. Stirling had already seen this in action on his own Runcorn scheme, disliked by most users and demolished within few decades. Some of the wiser architects at this time were already aware the inflexibility these systems would left for future generations, the of a simple RC Frame skeleton for Park Hill is the sole reason for its re-use by Urban Splash at this very moment.

To be fair to him, the Brief originally intended to build huge chunks (up to 1500 dwellings) of neighbourhoods which were feasible to build using large precast panels but uncertainty of South American politics and the difficulty of calling a huge crane for modest additions to dwellings were unrealistic proposals which people like Van Eyck and Charles Correa avoided by using small scale self-build type constructional systems.

Having made the comments above I have to point out that crafty ‘Jim’ came up with cracker of a type plan. It provided simple bases for natural growth in many combinations, providing four columns forming a permeable enclosure to the courtyard, itself a traditional feature in Peru and excellent source of natural ventilation, greenery and daylight. The originally built walls in large precast concrete panels were ideal to build against or to support any kind of future construction above these by residents. I understand a four storey structure has now been incorporated in and around Jim’s house forming a school. His signature porthole windows and rounded door heads have become a pointer to visiting architects to spot Jim’s contributions now almost buried in this DIY zoo/archaeological site this area now resembles. James Stirling would have laughed to see his original panel used in the same manner as beautifully crafted huge stone walls built by Inca civilizations were used to support later light weight structure for centuries after the original construction. This is what I would suggest a good example of history repeating itself.

“James Stirling interpreted the future behaviour of the families with certain amount of accuracy: Stirling houses were the most requested and those that display PREVI’s finest qualities of occupancy” Garcia-Huidobro, Torriti & Tugas.

Summing up can be best by quoting from Justin McGuirk’s article in Domus, April 2011, ‘The metabolist utopia’.

“Some of the houses are extraordinary works of transformation whose occasionally surreal suburban grandeur belies their setting. Tinted windows and hacienda styling many not meet with architects’ approval but they speak volumes about owners’ pride and aspirations. Therein lies one of PREVI’s great successes. People didn’t move out as their financial situation improved. Residents stayed and turned a housing estate into what feels like a middle-class community.”

The details of original competition are from AD April 1970; abstracts, quotes, layouts and photographs from Domus of April 2011. Small aerial inset of Stirling’s housing is copyright of Peter Land. All with thanks.