James Gowan’s House, Hampstead, London.

July 27, 2009

The last century produced score of private houses reflecting the aspirations of the owners or architects or often both, but if the budget was generous, the aim has always been to go up a notch or two in the chosen branch of ‘type and style’ for prosperity or in modern political lingo leaving a ‘legacy’ for the future generations.

This house has always been a bit of conundrum for building watchers. The client was a rich furniture manufacturer, Chaim Schreiber, who entrusted a young architect with a piece of land in most desirable part of London; almost limitless budget, an open brief – basically asking for a large dining-living space and lots of natural materials.

It would appear that this ‘gift’ of a job with freedom of action almost embarrassed Gowan, who decided to impose on himself a strict discipline of rectangular planning grid normally reserved for industrialised mass housing. It is possible that he anticipated that Schreiber may like to experiment with some modular furniture design for mass market in this house for future mass production.

Perhaps the clients ‘modesty’ and lack of ‘display’ encouraged Gowan to evolve a building which was as ‘style-less, class-less and scale-less’ as possible. This meant that the issues relevant to the mass housing, including the structure and building fabrics could be addressed and refined for future exploration serving a wider future role.

It is obvious that Gowan was keen to develop working and middle class housing and was fond of sensible Victorian standards of detailing and construction. It is possible that this project was a natural laboratory for testing his ideas and love for refined and practical detailing, bringing these strands together.

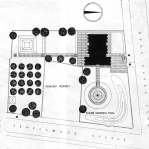

The resulting plan is very formal assembly of similar spaces in a flexible manner but despite this the building remains individualistic, open, airy and responds to the site well. The incongruity of the chosen style not only managed the building to become a good neighbour to the large existing Victorian Villa on one side but also prepared itself for an anticipated attack of a non-descript, post modernist neighbour on the other side of the house where the original swimming pool for Schreiber House once stood.

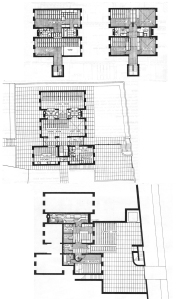

The module used (transferred for my younger friends in approximate metric dimension) was 900x450mm, subdivided into 225 and 150mm, throughout external and internal design including the fixtures and fittings producing a very well disciplined building.

I quote the following from an article in AJ of 14th July 1965, which is also the source of plans, sections and B&W photos seen here;

“A characteristic that most people would expect is that the building should be instantly recognisable as having a particular function. Here it is difficult to tell whether the building is one house or a group of flats (partly resulting from its scale) and, if it were not set among other houses, it might be mistaken for offices or even a church. However, it is an arresting building which looks as important as its Victorian neighbours. James Gowan was conscious of these problems and chose the unorthodox solution of deliberately concealing the organisation of the house and thereby the normal clues about its scale.”

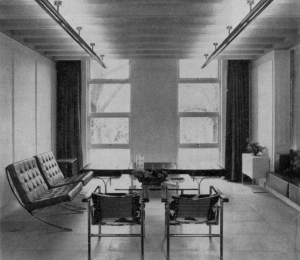

Floor Finish; San Stefano marble paving.

Floor Finish; San Stefano marble paving.

Ceilings; Generally artificial stone precast floor units.

Windows; Aluminium with double glazing. Air conditioned house.

Moulded ply storage units designed by architect and client. Most of the furniture, fittings, and even curtains, are based on the planning module.

Since its construction house has been sold twice and has been through some bad times. The surroundings have changed a lot. The dense growth of trees on the Heath obscures the original views and the present views below are oblique views of the house mainly from the footpath.

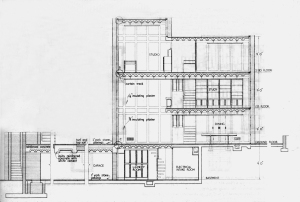

The lowest floor is for cars, maid and services, supporting the main living spaces facing Hampstead Heath and back garden. The terrace/podium facing the Heath protects the spaces from the noisy, busy road just outside.

The floor above contains the master bedroom and study and bathrooms.

The top floor houses three bedrooms, bathroom, sauna and studio for children.

If you look at the cross section, you would note that the trough section roof and floor units and the panelled in-situ plaster on elevation. The consistency of proportions by strict use of the chosen module is meticulous.

The precast floor units are also used to keep the junction between their thin edges and the aluminium anodised windows slim and delicate.