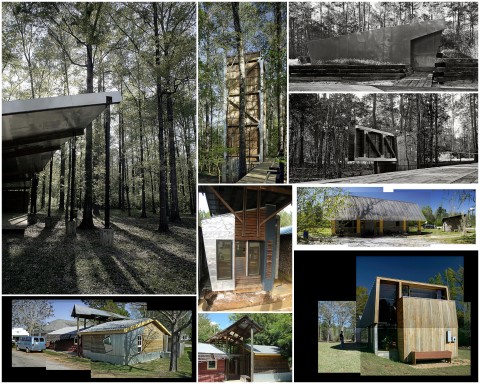

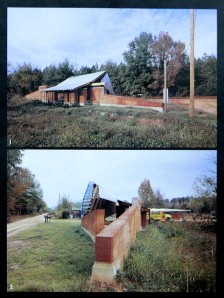

Samuel Mockbee, Rural Studio

September 8, 2013

Because of my long time interest in low cost housing, I kept coming across the name of Samuel (Sam/Sambo) Mockbee, associated with Rural Studio, Auburn University, in connection with the housing for poor Black communities in Hale County in Alabama. This was not an association I expected to come out of USA and decided to look into this unexpected phenomenon in more detail.

Because of my long time interest in low cost housing, I kept coming across the name of Samuel (Sam/Sambo) Mockbee, associated with Rural Studio, Auburn University, in connection with the housing for poor Black communities in Hale County in Alabama. This was not an association I expected to come out of USA and decided to look into this unexpected phenomenon in more detail.

This journey of discovery was exciting but turned sour when I heard of this remarkable man’s death from leukaemia at the age of 57 in 2001.

Europe is full of examples where architects, planners, philanthropists made significant contributions to develop social architecture (housing and schools) over last two centuries. Africa and Asia also saw some modest developments during late 20th century but the population, urban growth and poverty have given this problem urgency and much higher profile.

However, USA had no history of this ‘liberal–nonsense’, and for a white man to emerge in the heart of one of the most bigoted areas trying to ‘buck the trend’ was noteworthy.

This may be the right time to visit this man, his contributions and ambitions at the time when Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech is having its 50th birthday with consensus that dream has hardly come true.

Mockbee often quoted Alberti’s call for choosing between fortune and virtue, which he considered a question of value and principle. He thought architects to be by nature leaders and teachers, offering their ’subversive leadership’ for the shaping of environment, breaking up social complacency and challenging the power of status quo. He was repulsed by the thought that architectural profession was coming under the influence of consumer-driven culture and becoming part of the corporate world and corporations. For him architect should not wait to be told which problems need solution, architect should assert his own values that respect and are for the greater good.

“Architecture, more than any other art form, is a social art and must rest on the social and cultural base of its time and place. For those of us who design and build, we must do so with an awareness of a more socially responsive architecture. The practice of architecture not only requires participation in the profession but it also requires civic engagement. As a social art architecture must be made where it is and out of what exists there. The dilemma for every architect is how to advance our profession and our community with our talent rather than our talents being used to compromise them.”

Mockbee managed to disassociate himself from the bigotry of prevailing racial attitudes of American South and had a look at the effects of poverty and how architects can step over the threshold of injustice and address the true needs of neglected American family and their children who may also come of age without any vision of how to rescue themselves from the curse of poverty.

Mockbee once told one of his clients, a Catholic nun named Sister Grace Mary, that he’s not Catholic but “Christian by birth, Buddhist by philosophy, and heathen by nature”.

The main purpose of the Rural Studio has been to enable each student, tomorrow’s decision maker, to step across the threshold of misconceived opinions and to design/build with a ‘moral sense’ of service to community, being more concerned with the good effects of architecture then ‘good intentions’.

“On a triangular patch of land, next to the dirt road that serves as the hamlet’s arterial, stands a dramatic sculpture of glass and aluminum, cypress and steel and rust-red earth. This is the MasonsBendCommunity Center, designed and built as a thesis project by a team of fifth-year students at AuburnUniversity’s Rural Studio. The cost was approximately $20,000.

The building is processional in outline, gathering the community within arms of rammed earth, funneling them through a slender entrance sheltered by a fold of aluminum, and delivering them into a space that leads the eye through a fish-scale-glass membrane to the sky and trees beyond.” Chritine Kreyling

“Mockbee founded what is now called the Rural Studio, ‘Redneck Taliesin South’. Towards the end of his life he used to bring a group of his students to rural HaleCounty to design and build homes for the poor. One of the poorest regions in America, the county has more than 1,400 substandard dwellings, nearly all lacking electricity and running water. According to the 1997 Alabama County Data Book, about one-third of residents there live below the poverty level, with a per capita income just over $12,000 and an unemployment rate of 13 percent.

The Rural Studio not only fulfills an overwhelming need for decent housing but gives architecture students the kind of hands-on experience virtually all other educational institutions in the field lack. The houses are built for about $30,000 each using a variety of recycled and discarded materials (tyres, bottles) and funded mostly with grants from a local power company. Designed through a collaborative process involving students and local residents, the homes boast an unconventional modern flair that incorporates the cultural vernacular of the region. Lucy’s house made of 72,000 carpet tiles is now well known all over architectural community.

They may be cheap, but these are nice houses.” Mockbee thought that these should be good enough for him to live in with his family.

That Rural Studio is not only self-regulating, but it produces buildings of exceptional quality in direct response to the needs of the community, suggests that it has evolved from a teaching exercise to an alternative and compelling practical asset.

The New York Times published a feature on Rural Studio in December 2005 resulting in crowds of ‘camera/map carrying’ tourists seeking location of Mason’s Bend. With this kind of background the appearances start to matter, the church which was lacking frequent cleaning and was underused by the community became an embarrassment. This brought a changing attitude towards future community buildings and their future upkeep by apportioning responsibilities to various community members from start.

Freear wondered if Rural Studio has now reached its limit as a domestic housing endeavour, a well-intentioned educational experience benefiting a needy few, or could it evolve into a more serious and wide-ranging social project?

Projects are no longer conceived as isolated objects but links in a chain of essential social service.

The most recently completed final year projects exemplify this approach. Comprising a cell like lamella animal shelter, public park and hospital courtyard, rejuvenated as an attractive courtyard with expanded metal trellis serving staff.

Freear feels that he is also nearing his own limitations as a Director and recently started to take some classes at AA with an Indian architect Anapama Kundoo.

On a personal level looking back at the contributions Mockbee made fills you with admiration but its significance and impact on the root cause of poverty, resulting deprivation and alleviating it remains a mere ‘pin-prick’.

Suffice to say that few hundred houses and community buildings for a deprived community means a lot. However, the hope for me lies in the generations of young architects coming out of this ‘educational exposure’ with some idea of what ‘needs/survival’ really means to people they hardly knew existed.

I can only hope that even if some of them carry a small fraction of some of Mockbee’s generosity and wisdom the dream Mockbee had may be partly realized.

The information for this blog has been abstracted from Mockbee’s writings, interview and various magazine articles listed briefly below. The photographs are mostly attributed to my Flickr friends Ken Mccown and David Brown (odb). Their Flickr sites are well worth a visit.

Intereiew by Brian Libby April 2001; ‘Architecture without pretense’ by Christian Kreyling; ‘Community Hero’ by Jennifer Beck; Article by Andrea Oppenheimer Dean in Architectural Record.

Filed in Architecture, Architecture in USA, Indigenous Architecture, Modern Architecture, Regeneration, Self-Build Housing, Social Housing, Urban Renewal

Tags: Alabama, Anapama Kundoo, Andrew Freear, Aubern University, D.K. Ruth, Mason's Bend, Modern Architecture, Private Housing, Redneck Taliesin South, Sam Mockbee, Sambo Mockbee, Samuel Mockbee, Thomas Goodman

PREVI Experimental Housing Project, Lima, Peru. Part III

February 3, 2013

Earlier blogs have already looked at 4 submissions from internationally invited architects, this third blog looks briefly at other remaining entries, looking at their proposed designs and main objectives. Let us start by looking at 40 years of growth, starting as ‘immaculate architect deliverd new born babies’, growing out of their original clothes (as intended) and covering their bulging bodies with colourful and attractive garbs to feel good, comfortable and impress others.

Candilis, Josic, Woods (France)

The housing structure is a system of walls defining built and open spaces.

There are two different width of bays, smaller one is 2.7m wide, can be entirely covered forming single or two storey accommodation, the wider bay 4.5 m wide, forming courtyard, patios and living accommodation in different combinations to suit immediate and future needs of occupants. The land can be traded off between adjacent owners to suit their particular needs.

The basic units at the start are all of equal size consisting of two small bays and one large one, and come ready with masonry walls, slabs and concrete beams with water and drainage points and a certain amount of space is enclosed.

The streets serving the dwellings can be orthogonal or diagonal interdisperced with public squares and gardens. Shops can be formed within individual dwellings as happens in existing barriadas.

In early stages of development private cars may be limited to perimeter of the housing area, while service vehicles will use pedestrian ways but these arrangements can be readjusted to suit future car ownership demands.

Charles Correa (India)

Correa said that the project grew from the following four objectives:

(1) Highest possible density commensurate with (2) Individual landownership;

(3) Minimum road and servicing cost; (4) Pedestrian /vehicle separation.

An arrangement of narrow row houses with access at both ends provided the logical answer both to vehicle segregation and minimization of service runs with porches and backyards acting as transition areas between pedestrian and car access and the interior of the houses along diagonal road and footpath routes so as to exploit the prevailing wind for ventilation purposes – aided by airscoopes over the central area of each house – and to achieve optimum orientation with respect to sunlight. Tree planting along pedestrian and service roadways can be employed to modulate sunlight and natural ventilation as well as traffic noise from the central thoroughfare.

The service structure of schools, shops, and church and recreation areas is strung out in a disjointed diagonal moving in the opposite direction to the footpaths and roads. They take the form of the covered shaded areas set in well ventilated clearings and can be easily reached on foot as they can be by vehicle. The shops can be serviced from cul-de-sac service roads. From individual porches one can walk along pedestrian ways until these join the central spine of patios culminating in the central church and shopping area.

There is a single underpass linking both halves of the site across the central area.

The houses themselves are designed in such a way that they can either be built by their future occupants, with the assistance of the authorities as regards prefabricated elements, subsidies, skilled labour etc.: or they can be completed by the authorities themselves and sold to individual families. The former option would allow greater flexibility and, bearing in mind the efforts have been made to minimize the number of constraints that would be necessary under the circumstances.

Narrow plots resulting in narrow frontages, in architects mind ensured that the façade to be ‘controlled’ was very small and set well back into the porch.

The short span housing offered considerable structural flexibility which could be exploited by the occupants. Further flexibility was offered by building the first stage development to be on ground floor, incorporating a front porch, living/dining area, bedroom, central patio, bathroom, kitchen and a small service patio at the rear. This was considered sufficient for a young family with one or two children. The future stages could add first floor bedrooms and bathroom.

Correa’s ‘interlaced’ scheme generated by the saw-tooth configuration of the anti- seismic outer wall is orientated along the axis that is most conducive to natural ventilation. The major changes have been made on the scale of the city block. Individual owners have now aligned their units along the street front.

“Without malleability you can not have cultural expression-

all you can get is a top-down notion of how people should live” C.C.

Esguerra, Saenz, Urdaneta, Samper (Columbia)

Project tries to create neighbourhoods units with high densities/low rise but individual ownership. This approach also reduces combining services and communications. The supervision of open spaces, security of motor cars, play areas is also assured through this community spirit.

Individual plots are square maximising the flexibility of layouts, reducing party walls, enclosing pedestrian routes with easy access to cars.

There are 20 unit designs available depending on locations within layout, service areas and staircases. The following standard structural components using a 50 cm module are extensively used;

- A standard pre-stressed concrete tee beam and accompanying hollow brick infill elements.

- Prefabricated concrete lintels and porch section and perforated bricks.

- A standard open web steel roof joist with steel support columns to support ‘Eternit’ roof sections.

- Standard prefabricated sinks, wcs, washbasins and showers.

- standardised water, gas and electricity installations.

- Metal doors and window frames and terrazzo stair treads.

Oskar Hansen and Svein Hatloy (Poland)

Oskar Hansen and Svein Hatloy (Poland)

Earth banks and areas of planting protect the project from the main traffic route.

This scheme avoids using neighbourhood areas as the scheme avoids the formation of hierarchical structures and offers parallel opportunities for all.

Each single unit is placed in close proximity to a sheltered open space to allow free pedestrian movement and play spaces near homes. These paths/private open spaces are connected with the central servicing zones ensuring a steady pedestrian traffic.

All houses are within ten minutes walk from the central rapid-transit route with adjacent parking areas, services and recreation facilities. Construction is intended to be gradual (north-east corner to south-west) to enable progressive occupation without excessive disturbance.

The dwellings are designed to be built in two stages in variety of ways, the first consist of primary structure, building the prefabricated concrete elements placed by a three-ton crane. The secondary structure stage of completion is carried out by tenants themselves by using lighter elements of clay or concrete blocks, lintels, wall panels, partition, windows, woven fibrous screens and textiles, all capable of assembling in number of combinations to suit occupant’s needs.

The structural walls incorporate storage recesses with doors and ventilation to open air, while shaded areas cool ingoing air.

The open nature of plan still provides acoustically quiet areas in the centre of the house, where the private rooms are situated.

J.L.Iniguez De Onzono and A.Vazquez De Castro (Spain)

The site is divided into ten neighbourhoods, each of about 500 dwellings.

A 3 m wide main pedestrian street runs centrally connecting groups of dwellings.

Groups of one-family houses are standard plans around internal and service patios.

Upper floors are planned alongside access alleys. A circular staircase links the two floors.

The structural system of prefabrication provides a series of permanent shuttered elements for poured reinforced concrete (walls, pillar, and beams).

The main structural grid used is 36m x 36m, derived from practical requirements. The structural grid is separate from the internal module making it independent from internal additions and changes.

The plan of dwelling type is based on a functional separation of service and kitchen spaces, general spaces, and sleeping spaces. This offers maximum flexibility to suit future needs of occupiers who will determine the forms themselves.

The boundary walls of all dwellings are built first. The simplest dwelling thus consists of an undivided space, with water and drainage laid on in the service yard, which at the outset will serve as a kitchen. From this starting point the owner fills in and extends his house. Sanitary and Kitchen fittings are fixed using standard components. Services are grouped to avoid long installation runs.

The structural system has shallow concrete foundation pads, a floor slab resting on the ground and concrete columns and beams, supporting a corrugated asbestos roof.

All basic dwellings are single storey, when the upper storey is required; the original roof acts as shuttering for concrete.

There is no traffic within each developed area, apart from service traffic which penetrates on several wider roads. Parking areas in the first stage are mainly reserved for public buildings.

Aldo E. Van Eyck (Netherlands)

Aldo E. Van Eyck (Netherlands)

The urban structure formed by the housing is derived from a clustering principle which operates independently of the dwelling type employed. The plot shape does not correspond to the octagonal shape of the houses, so squares, rectangles, rhomboids and free forms could be employed with equal ease. The chief advantage of the hexagonal house with its low perimeter wall is that it discourages further building by the inhabitants in any direction which would result in the loss of external spaces or internal light a frequent development in self-build barriada housing. In this sense the houses are designed so that further free development cannot work against the best interests of the occupants.

The layout is characterized by thick bands of clustered housing separated by a small number of roads placed as far apart as possible. Each band is six plots deep presenting a wall of houses made up of rows of six and two, or five and three dwellings, to the principle avenue, which is itself developed more or less symmetrically so as to achieve a more monumental character. The access footpaths serving the bands of housing have a more informal aspect which clearly differentiates from the main thoroughfares. Climatic considerations affected this layout as traffic – which is insensitive to climate – runs from east to west, whilst the pedestrian footpaths run south-east to north-west or north-east to south-west so as to take advantage of cooling breezes during the hot summer. Protection from a winter winds is achieved by means of the block staggering shown on the plan.

The arrangement of paths described above allows the breeze to penetrate deep into each band of dwellings, a process facilitated by the lateral staggering of the houses. Both house types1 and 2 are designed to take advantage of this air movement by permitting through ventilation to all interior and exterior private spaces. The triangular patios discourage building over in the manner described above, so that the achievement of a genuinely urban character – instead of a suburban – can be realized. All schools and service facilities are accessible along the diagonal pedestrian paths whilst a variety of safe play spaces for children, communal lawns, plazas with fountains and other open spaces are grouped at the ends of the footpaths in full view of all houses for security.

Car parking is provided along the principal avenues and also in certain areas off the footpaths.

In the design of the houses an effort has been made to avoid the appearance of an industrially produced minimum house – which carries with it a stigma not easily overcome by the inhabitants of former barriadas. Instead an effort has been made to build a measure of flexibility into dwellings which can not only interpret traditional and modern living styles but also adjust to different room arrangements corresponding to individual family requirements.

“It would be a grave error if pre-designed and partially pre-constructed urban environments such as this pilot project proposes should counteract the growth and development of the barriada idea and practice, instead of stimulating it through the erection of improved dwelling types, construction systems and overall community planning.” A.v.E.

Prior to taking part in the competition Aldo van Eyck visited Peru where he observed that in local houses women were at the heart of the home, he placed the kitchen in the centre of the floor plan. He also took a more proscriptive approach to how the owners should expand, creating diagonally walled courtyards to discourage people building on top of them. He failed of course. Outside space is not sacred to a family of eight with another generation on the way.

One of my favourite photos from Domus shows this combinaton of sophisticated Danish technology, precision and grace, embellished and enhanced by this proud couple, who met Knud Svensson as they occupied this house they adored from the first day. Architect promised that one day he would come back to build them a first floor extension to match what they liked, but unfortunately that never happened.

Collective/Community External spaces in PREVI

“Though many years have passed, bearing in mind the premise that Peter Land’s team addressed the influence of each participant throughout the design process, the composition of these elements suggests the contribution of Aldo van Eyck.

This assembly of highly static, geometric abstract objects, their gravity-defying impression of lightness and the sculptured border all recall the playgrounds of post-war Amsterdam designed by Aldo van Eyck for Amsterdam’s Department of Public Works. Van Eyck addressed the issue of interstitial voids and defined space and place, producing interventions that were both numerous and ephemeral. His ambition of creating a space for children that was “more durable than snow” was realized in the desert of Lima.

It is surprising to note how the constant transformation of the housing units distracted architecture reviewers, while the collective spaces attracted hardly any attention. The collective space, immaterial and flowing, is the most determinant and lasting element of the PREVI.” Quote from an excellent dap paper Issue 9 by Marianne Baumgartner on collective spaces. http://www.architecturalpapers.ch/index.php?ID=90

“EL TIMPO CONSTRUYE! TIME BUILDS” by Fernando Garcia-Huidobra, Diego Torres Torriti and Nichlas Tugas Barcelona 2008. A rather difficult book to get hold of, but I understand most of the Domus graphics and details are attributed to this book

Domus April 2011, report by Justin McGuirk.

Julian Salas & Patricia Lucas from openhouse international vol 37 No 1 ‘The validity of PREVI, Forty years on.

Filed in 70s Housing, Architectural Competition, Courtyard Housing, Developing Countries, Housing in 60s, Indigenous Architecture, Informal Urban Housing, Regeneration, Self-Build Housing, Social Housing, Town Planning, Urban Renewal, Vernacular Architecture

Tags: "Candilis Josic and Woods", "German Samper", "Iniguez de Ozono and Vazquez de Castro", "Knud Svensssons", "Marianne Baumgartner", "Oskar Hansen and Svein Hatloy", "Precasting", "Rationalised Masonry", "Toivo Korhonen", 60s Housing, 70s Housing, Aldo van Eyck, Charles Correa, Experimental Housing, High Density Housing, Modern Architecture, Peter Land, PREVI, Rationalised Construction

PREVI, Experimental Housing Project, Lima Peru. Part II

January 20, 2013

Short description of 3 winning entries (Atelier 5, Kikutake-Kurokawa-Maki and Herbert Ohl), and one entry (Christopher Alexander) supported by a split jury.

Having covered the background of PREVI, a glimpse of the competition Brief and the resulting buildings, with particular reference to James Stirling’s proposals, were explored in my first Blog, now I would like to go through the original winning entries and their progress over last 40 years.

You would recall that the jury chose 3 winning projects from 13 International architects in 1969. Atelier5; Kikutake-Kurokawa-Maki; and Herbert Ohl were the official winners but there was a split in the jury and Centre for Environmental Structure by Christopher Alexander was considered by this jury to be worthy of a winner.

Jury thought that Atelier 5 scheme used an interesting method (possibly economical) of construction using pre-cast concrete panels small enough to be built on site and manhandled for wall and roof construction. They considered that two storey house plan appeared complex with patios and internal spaces. The external communal spaces and separation of traffic was well liked.

In a recent interview Alfredo Pini of Atelier 5 said that their invitation to PREVI was a result of their successful Halen project. They were full of praise for the aims, objectives and the process of the competition. The implementation of their 25 units took place in accordance with their plans but the distance and complexities made the involvement difficult towards the end. They were pleasantly surprised to see the attention and care given to external public spaces after decades of use.

Pini did not consider the present situation a chaos – “…it is a fine chaos. I have nothing against it – in fact, I positively like it. That is a positive drive…. The extensions and interventions of inhabitants were quite good.”

Kikutake, Maki and Kurokawa and Associates also used pre-cast concrete system with different loadings which also included foundations, again considered well worked out and likely to save costs. House plan grouped service areas with potential of local industry producing equipment/units for Kitchen, Toilets and storage in future.

The external spaces in this scheme also separated cars from pedestrians but some jury members considered the spaces were possibly too extensive for effective use.

Fumihiko Maki in a recent interview recalls the original brief. The large growing families would reflect the growth of houses, an important metabolist concept. He welcomed the changes to the houses but was concerned about the extra floors being built on modest original foundations in an earthquake zone.

Herbert Ohl scheme was problematic from start. Design was sophisticated use of extensive large pre-cast elements using complex arrangement resulting in a shell which could accommodate internal changes with ease and flexibility.

There was proposal for an underground ‘service spine and car parking’.

Minority jury disliked Ohl’s scheme and considered it regimented, inhuman and expensive.

The ‘travelling crane’ in their view became a designer rather than a useful tool.

Architect anticipated a democratic interchange between human and technological factors, stimulating multiplicity, flexibility, micro and macro relations; … all using dimensional and functional modules. The mobile crane was able to provide universal frame structure at any time without disturbing the community.

As feared, the complexity and difficulty of producing even a small part of this scheme failed to be built in the ‘sample’ project constructed under Peter Land’s supervision.

The science fiction approach may have been exciting to explore but was very unrealistic and removed from the objectives of the competition. I am surprised it was one of the 3 schemes chosen as winners.

Interview by Martanne Baumgartner and Tomeu Ramis, ETH Zurich.

This split jury thought that Christopher Alexander’s proposal was a ‘milestone’ which addressed the brief and Peruvian conditions and produced an imaginative solution for low income housing and offering maximum freedom of individual choice. The praise continued “….a freshness of approach, a commitment to the dignity and worth of individual , a recognition and understanding of the complex linkages between the individual, his family, his belongings, his neighbours and the entire community are implicit in each part of this proposal.”

The building system uses fewest standard components to provide maximum variety and choice of solutions… the proposed use of bamboo, urethane, and sulphur structural members may not be new or proven but was in keeping with the spirit of this competition.

It is difficult to explain the concepts behind the ‘cell structure’ of the housing layout in this short introduction but it is a fascinating report to study if you can lay your hands on it.

The house layout considers various traditional aspects of Peruvians social/living habits.

The house construction was aimed at using local materials and traditions where possible. The foundations were floating slabs supporting load-bearing walls and a lightweight plank and beam floor/roof. An ingenious interlocking mortar-less concrete-block for wall construction, reinforced with sulphur, with cavity for plumbing and conduits. The planks and beams are made of urethane foam-plastic and bamboo, reinforced with sulphur-sand topping; all are earthquake resistant methods of construction.

Information attributable to the following sources;

AD 4/70, Competition drawings and Thick Walls AD Feb 1968; Domus, April 2011,’ Metabolist utopia’; ‘The validity of PREVI, Lima, Peru, 40 years on’ by Julian Salas and Patricia Lucas.

Filed in 70s Housing, Architectural Competition, Courtyard Housing, Developing Countries, Housing, Housing for growth, Housing in 60s, Indigenous Architecture, Informal Urban Housing, Regeneration, Self-Build Housing, Social Housing, Town Planning, Urban Renewal

Tags: 60s Housing, Alfredo Pini, Atelier5, Centre for Environmental Structure, Christopher Alexender, Domus, Experimental Housing, Herbert Ohl, High Density Housing, Housing, James Stirling, Julian Salas, Justin Mcguirk, Kikutake- Kurokawa-Maki, Lima, Martanne Baumgartner, Modern Architecture, Patricia Lucas, Peru, Peter Land, Precast Concrete Blocks, Precast concrete Panels, PREVI, Rationalised Construction, Social Deprivation, Social Housing, Tomeu Ramis, Traditional Construction, Travelling Crane

PREVI, Experimental Housing Project, Lima, Peru. Part I

December 12, 2012

Introduction to Architectural competition, Brief and building of samples of entries focused on James Stirling’s proposals. 1965 to present.

“PREVI, Spanish initials for “experimental housing project”, was conceived in Lima in mid 60s. In 1965 Peru’s Architect president Fernando Belaunde Terry began consultations to explore the ways of controlling the flow of people seeking urban living and spread of self-build informal barriadas in urban Peru. The proposals were submitted to UNDP in 1966 and approved in 1967. The work started in 1968 with the intentions of carrying out three pilot schemes over three years.

Three original winning schemes could not be built in accordance with earlier intended scale or details. In the end jury decided that the best way forward was to build all 26 submitted proposals because of their high quality. Most of the competition invitation work and implementation of building of 24 out of 26 schemes was masterminded and overseen by the British Architect Peter Land.

The forty years that have lapsed in the interim and the ongoing transformation of the homes by their dwellers afford an opportunity to reflect on the suitability of the construction technologies proposed in the competition. Ongoing growth and the rationalization of construction methods were two of the basic premises underlying the competition. The remodeling that has taken place in the interim stands as proof of the success of the first premise, but the use of traditional techniques to build the additions calls some of the most sophisticated proposals for industrialization into question. At the time, the tendency was to rely on large-scale industrialization, as can be seen in the German, British and Polish architects’ proposals. Nonetheless, many of the PREVI proposals opted for rationalizing construction and precasting short series of small elements, rather than huge three-dimensional members. In the situation presently prevailing in Latin America, the viability of some of the technological proposals deployed in the PREVI might be profitably revisited.”

Abstracted from a paper by : Julián Salas and Patricia Lucas (Italics additions by self)

The process of building in PREVI was originally intended for large scale provision of housing, which was to create a transformable core model with one room and provide basic utilities for the unit. The idea was that the new owners were free and encouraged to expand in accordance with the needs of their growing families and their own financial situation. In these new projects the hope was that rather then using salvageable and recycled materials suitable and dependable construction would be used and paid for by the owner/occupants. This process allowed the owners tenants to control their own social, family and cultural needs making them more involved and motivated towards the project. It was also hoped that the ideas generated by the competition would introduce new methods of creating energy efficient, seismic resistant and cost effective building techniques.

The architects and project managers under the lead of Peter Land took a holistic approach in building the fruits of this rare International competition for social housing.

“If Weissenhof Siedlung is the natural childbirth of social housing in the First World, PREVI is the coitus interruptus of Third World housing”

I sincerely hope that success of this project (although far from pretty in comparison with seductively dressed social housing schemes on offer in better-off countries) hidden in a remote part of world will offer useful lessons of construction and design to professionals and students with strong social conscience. The lessons should be absorbed and filtered down to educational curricula throughout the globe to inspire future generations of architects in solving the international housing dilemma facing millions throughout the world.

General notes.

The Government of Peru formulated an experimental project in housing which had an objective of developing new concepts of forming experimental neighbourhoods and techniques utilizing Peruvian and foreign experience. In 1965 its Architect president Fernando Belaunde Terry began consultations to explore the ways of controlling the flow of people seeking urban living and spread of self-build informal barriadas in urban Peru. The proposals were submitted to UNDP in 1966 and approved in1967. The work started in 1968 with the intentions of carrying out three pilot schemes over three years.

In PREVI, 13 internationally renowned architects were commissioned to develop prototypes of urban housing that would internalise programmes for any future transformation. Thus each unit contained the terms of its own growth, recognition of the value of the dynamic of growth adopted in the informal slums. In contrast to a growth model based on large, out of scale gestures – from megastructures to gigantic superblocks – the PREVI experiment fielded new dynamics based on a model of low-rise, high- density housing.

When in 1968 a military coup led to the overthrow of the president-architect who had promoted the PREVI project, the involvement of UN prevented the project’s cancellation.

The jury met in 1969 and having chosen 3 winning projects from 13 International architects ( Kikutake-Kurokawa-Maki 4; Atelier 5 and Herbert Ohl), resolved to initiate the construction of all but two of the proposals in 1974, the first phase of 500 units was finally built and left to its fate of growth and progressive oblivion.

The 13 invited International architects were; Toivo Korhonan 6; Charles Correa 1; Christopher Alexander 8; Iniguez de Ozono & Vazquez de Castro 10; Georges Candilis; Alexis Josic; Shandrach Woods 13; James Stirling 7 ; Esquerra & Samper 2; Aldo van Eyck 9; Kikutake, Kurokawa & Maki 4; Svenssons 3; Hanson & Hatloy 11; Herbert Ohl 12; Atelier 5 5. (Jose Antonio Coderch from Spain was one of the Jury members)

The numbers after the name refer to general layout marked with numbers. The brown areas on the layout indicate subsequent additions extending the original built forms.

Summary of the brief.

Mandatory requirements were that each dwelling plot was to be between 80-150 m2, of which dwelling was to occupy between 60-120 including all floors.

The buildings initially were to be 1 or 2 storeys designed to support the third floor and were to be based on100 mm module. The ideas were to explore and develop techniques in architecture and construction within general area of low rise, fairly high density and compact housing in terraced, row and other formation. High rise developments were ruled out.

Detailed designs of dwellings were to be submitted with only a schematic general design for the community. All dwellings were to be flexibly planned for eventual accommodation of eight children of different ages, and one elderly couple, in addition to the owners.

Each dwelling had to provide living, dining, kitchen, bedroom(s), bathroom(s) and service patio. The relationships between rooms and external spaces were defined. Roof areas were required to be suitable for outdoor space.

The dwellings were to be conceived not as a fixed unit but as a structure with a cycle of evolution with appropriate construction technology to achieve this aim.

The initial basic unit was to be built by the main contractors and technical advice and assistance in building will be made to families completing their houses.

Car parking spaces were required to be on individual plots although at this time most of the families did not own cars.

James Stirling’s Proposals.

After the ‘first build’ by the contractors it was intended that the house should be completed at ground level and above by house owners in self-building styles.

The growth plan drawing shows in stages of self-building a 4P house becoming a completed ‘one storey house’ (8P+) considered the most typical method of growth. Thereafter expansion takes place on the floor above, either as a separate dwelling or, in the case of a large family, as additional bedrooms and living spaces, in which instance part of the ground level accommodation could be used for other purposes (i.e. shop or garage etc.).

When the house was at its smallest (4P), the kitchen, dining and living area were shown combined. As the house increased in size to approximately 6P the dining and living areas were separated from the kitchen by a wall and doors. This wall (knock-down or moveable) appeared in a new position when the house becomes 8P and 8P+, increasing the living space of the house as the family size grows.

Each house had two front entrance doors. One door led directly into the living area (social/traditional), the second (functional) into the house circulation area leading via the staircase and garden patio through to the service patio.

All rooms were planned with through ventilation i.e. separate openings on opposed walls to create cross draughts.

The ‘first-build’ by the contractor takes advantage of the large-scale initial production (cost and speed of erection) and was an assemblage of precast concrete walls and floor units. Party walls and outside perimeter walls were of sandwich construction and were precast units rising from ground beams incorporating windows and door openings and also parapets – these were crane erected.

Roof/floor units were lightweight r.c.beams with hollow pot infill which could be man erected allowing self-help methods of construction t as expansion was required.

Just as the individual rooms of the house were grouped around the garden patio, similarly the various sizes of house groupings were linked with differing scales of social and community space.

The hierarchy grew from the individual house to the immediate neighbours by making an initial group of four houses above common party walls (and common services) grouped around the service patios. These clusters of four house units were then grouped around a common entrance patio forming 20 or 21 houses. Thereafter this larger group becomes the basic cluster unit forming the neighbourhood (approximately 400 houses) and was related to access roads and car parking. There are four such neighbourhoods the allocated site area (1500 houses) and each is separated by a Public Park (planted, informal garden valleys) in which were to be sited the schools etc.

Flanking the approaches to the neighbourhood parks and enclosing the end of the housing areas were reserved for commercial buildings, shopping and community centres.

Stirling in 60s.

James Stirling was well informed as far as CIAM and its views on housing were concerned. He had already carried worked on proposals for a village scheme using vernacular and simple construction. At this time Europe was swamped with large concrete panel housing construction showing off their economy due to scale and rapid construction. Stirling had already seen this in action on his own Runcorn scheme, disliked by most users and demolished within few decades. Some of the wiser architects at this time were already aware the inflexibility these systems would left for future generations, the of a simple RC Frame skeleton for Park Hill is the sole reason for its re-use by Urban Splash at this very moment.

To be fair to him, the Brief originally intended to build huge chunks (up to 1500 dwellings) of neighbourhoods which were feasible to build using large precast panels but uncertainty of South American politics and the difficulty of calling a huge crane for modest additions to dwellings were unrealistic proposals which people like Van Eyck and Charles Correa avoided by using small scale self-build type constructional systems.

Having made the comments above I have to point out that crafty ‘Jim’ came up with cracker of a type plan. It provided simple bases for natural growth in many combinations, providing four columns forming a permeable enclosure to the courtyard, itself a traditional feature in Peru and excellent source of natural ventilation, greenery and daylight. The originally built walls in large precast concrete panels were ideal to build against or to support any kind of future construction above these by residents. I understand a four storey structure has now been incorporated in and around Jim’s house forming a school. His signature porthole windows and rounded door heads have become a pointer to visiting architects to spot Jim’s contributions now almost buried in this DIY zoo/archaeological site this area now resembles. James Stirling would have laughed to see his original panel used in the same manner as beautifully crafted huge stone walls built by Inca civilizations were used to support later light weight structure for centuries after the original construction. This is what I would suggest a good example of history repeating itself.

“James Stirling interpreted the future behaviour of the families with certain amount of accuracy: Stirling houses were the most requested and those that display PREVI’s finest qualities of occupancy” Garcia-Huidobro, Torriti & Tugas.

Summing up can be best by quoting from Justin McGuirk’s article in Domus, April 2011, ‘The metabolist utopia’.

“Some of the houses are extraordinary works of transformation whose occasionally surreal suburban grandeur belies their setting. Tinted windows and hacienda styling many not meet with architects’ approval but they speak volumes about owners’ pride and aspirations. Therein lies one of PREVI’s great successes. People didn’t move out as their financial situation improved. Residents stayed and turned a housing estate into what feels like a middle-class community.”

The details of original competition are from AD April 1970; abstracts, quotes, layouts and photographs from Domus of April 2011. Small aerial inset of Stirling’s housing is copyright of Peter Land. All with thanks.

Filed in 70s Housing, Architectural Competition, Architecture, Cortyard Housing, Developing Countries, Housing, Housing for growth, Indigenous Architecture, Informal Urban Housing, Modern Architecture, Private Housing, Regeneration, Self-Build Housing, Social Housing, Town Planning, Urban Renewal

Tags: Aldo van Eyck, Alexis Josic, Atelier 5, Barriadas, Charles Correa, Christopher Alexander, CIAM, Domus, Esquerra & Samper, Experimental Housing, Fernando Belaunde, Georges Candilis, Hanson & Hatloy, Herbert Ohl, High Density Housing, Housing, Informal Housing, James Stirling, Julian Salas, Justin Mcguirk, Kikutake- Kurokawa-Maki, Lima, Ozono & Castro, Patricia Lucas, Peru, Peter Land, Precast Concrete Blocks, Precast concrete Panels, PREVI, Shadrach Woods, Social Deprivation, Social Housing, Svenssons, Toivo Korhonan, UNDP, Urban Renewal

Louis Kahn, Lesser known early work.

October 14, 2012

Louis Kahn’s work before Yale University Art Gallery (1950) is not very well known and publicised. However it is worth remembering that he was practicing since early 30s.

Louis Kahn served as a consultant to the Philadelphia Housing Authority and the United States Housing Authority in 1930s. He had a deep sense of social responsibility and was very interested in providing low cost housing.

He also worked with European émigrés Alfred Kastner and Oskar Stonorov.

In the early 1940s Louis Kahn associated with Stonorov and

George Howe, with whom Louis Kahn designed several wartime

housing projects such as Carver Court in Coatesville (composite; top left), Pennsylvania (1941-1944) and Pennypack Woods in Philadelphia (1941-1943). His last scheme of this period was the public housing in Philadelphia’s Mill Creek Housing project (1951-1963).

In late 40s Louis Kahn‘s career took-off when he established an independent practice and began to teach at Yale University and then at the University of Pennsylvania as Professor of Architecture (1957-1974). During those years, his ideas about architecture and the city took shape and early work of idealism that followed the international modernism was re-examined and reassessed by him and we all know the impact that produced on architectural history for the rest of 20th century.

I visited Canada and USA as a student in 1967 and attempted to see as much of his work as I could. On my visit to Mill Creek Housing I could not help noticing boarded up properties and a general feeling of deterioration. Few years ago when I learnt that the Estate was demolished, I was surprised and rather puzzled but put it down to possible social deprivation, poor maintenance and ‘sink status’ – a situation one comes across in Britain social housing frequently.

A quick search on internet started to unfold a different story which may be worth noting. Apparently the apartments were built on top of the Mill Creek flood plains. In 1961 several blocks of houses collapsed causing some deaths and as a result 111 houses were condemned and demolished. There were also three 17 storey tall residential blocks, also designed by Kahn in a subsequent phase see composite top right-bottom), which I am informed were a social disaster as far as accommodation was concerned were also demolished.

In the photo on top, Carver Court B&W photo attributed to Wiki Arquitectura. Site layout from http://www.design.upenn.edu. Mill Creek Housing photo from from’ In the Realm of Architecture’.

All other individual photos from my 1976 visit.

Filed in Demolished, Housing, Modern Architecture, Social Housing, Town Planning

Tags: "Alfred Kastner", "George Howe", "Louis Kahn", "Philadelphia", "USA", Carvar Court, Coatsville, flood-plain, Housing, Mill Creek Apartments, Mill Creek Housing, Modern Architecture, Modern Housing, Oscar Stonorov, Pennsylvnia, Pennypack Wood, Social Housing

Neath Hill, Pennyland. Earley housing in northern Milton Keynes

October 9, 2012

Wayland Tunley intentions from the start were to have a wide variety of uses and housing on this site as he saw the dangers in housing 3000 people in a repetitive layout lacking amusement and joy.

A clearly understood street, cycleway and pedestrian network were to lead to a lively central area to be shared with the adjacent grid of Pennyland and to be linked to the city via the grid road. He intended to provide maximum variety of public areas surrounded by house types and designs which people were familiar with and liked. The layout consisted of varied building designs around streets, mews, landscape styles, offering surprises and vistas.

The trap of using unfamiliar building materials and contrived forms was also avoided by using red bricks, tiled roofs vernacular throughout the grid where the topography of this prominent site offered the variation sought by the designers to achieve a village plan within the grid with entrances marked with gate piers, timber oriels, lanterns, balconies, pergolas and its own ‘green’ and clock tower

A wide variety of mostly wide fronted one to three storey houses was employed often placing living rooms on first floor to take full advantage of the views. Most of the houses were originally meant for rent, some for sale. There was also specialist accommodation for Spastics Association, employment office, shops, a Pub, health centre, housing for elderly, schools. This variety building types was fully utilised to provide variation of scale and roof heights.

The streets and mews are named after old crafts, within context of a ‘village vernacular’ of a comprehensive newly designed picturesque village community lost within a modern large new city designed for cars.

The local centre lies within Neath Hill but casts its visual net to cover the adjacent grid of Pennyland and indeed announcing itself to the speeding motorists on the main grid road. Neath Hill and Pennyland are special grids as the local centre shared by the two adjacent areas is a departure from norm and addresses the main grid road to break the MK planning rule of hiding the centres in the heart of grids surrounded by housing and a lush belt of hedges and trees to keep the housing grids secret and private to the local population.

Wayland Tunley is the main ‘conductor and composer’ in this area. The housing varies from simple and plain to celebratory and elaborate, depending on the placement within a very rich mix of public spaces and pedestrian circulation. The hidden secret of these grids lies in the joy of walking on footpaths winding their way through matured landscape reminding you of intimate country lanes, village greens, with beautifully framed views of building landmarks. Grand Union Canal has also been included in giving an extra boost to this subtle experiencing of marriage between the social architecture and the best traditions of British informal landscaping by offering a mini ‘Venetian Corner’ with a British twist to the complete surprise of casual newcomers.

By the time Pennyland come to the drawing board, the energy conservation was becoming a significant issue. The first phase was built to higher standards if insulation and employed quite a few energy conservation experiments and studies.

Wayland Tunley left MKDC in early 1980s and won a competition to build canal-side housing (I assume as a builder/developer partnership) which used traditional canal side architecture and language of Netherfield very effectively. Housing built further away from Neatherfield was carried out by other architects and developers.

Filed in 70s Housing, Architectural Competition, Buckinghamshire, Housing, Milton Keynes, Modern Architecture, New Town, Private Housing, Social Housing, Town Planning, Vernacular Architecture

Tags: Canal-side Housing, Derek Walker, Housing, Housing in Britain, Landscape, Milton Keynes, MKDC, Modern Architecture, Netherfield, Nigel Lane, pedestrian network, Private Housing, Social Housing, Traditional Construction, Wayland Tunley

Galley Hill, Greenleys. Early Housing in northern Milton Keynes.

October 8, 2012

The design team dealing with northern Milton Keynes was led by Nigel Lane and Wayland Tunley. They dealt with sensitive infill schemes in Stony Stratford (Cofferidge Close) and did infill projects in tightly built railway town of Wolverton including the Agora. (see Blog: Agora, Wolverton MK: February 19, 2010)

Galley Hill was one of the first large housing schemes completed in 1971-72. At this point the problems of overheated building industry became apparent. The required speed of building new houses was not available and to meet the requirements, simpler layouts were needed along with the introduction of industrialised methods of construction whenever possible.

The small groups of terraces forming the public spaces were treated in fairly homogeneous manner as far as use of colours and finishes of horizontal boarding and design of doors and windows was concerned.

However, as happened in other places, the subsequent private ownership of a large number of houses ensured an introduction of patch work of varying colours and materials to display individuality of their new owners, weakening the architectural coherence originally envisaged.

The pitched roofs helped in many ways – disasters of leaking flat roofs of southern flank housing schemes were not experienced and roof scape also helped to unify the appearance.

The densities were low and compared to modern housing developments these Parker Morris standard houses and large open spaces look almost lavish.

Buckinghamshire County Council was responsible for designing and building schools in Milton Keynes and one of their gifted architects, Brian Andrews, worked closely with MKDC planners to build a traditionally built school closely integrated with the roads and footpaths. There was some bold ‘arts and crafts’ inspired brick detailing and a friendly open layout. Unfortunately the subsequent vandalism has meant that fences and gates have denied easy access.

Greenleys housing is more formal, using car free courtyards on either side of car parking areas or courtyards large enough to bring cars into attached garages and car parking spaces. These schemes were worked out and built fairly quickly. The warm coloured bricks and pitch roofs were also a far sighted decision for this period. Landscaping, as usual is of high standards unifying the whole scheme.

Buckinghamshire County Council built another traditional looking school here. Ivor Smith built the Local Centre with Community and Sports facilities at low level and housing above.

Both are shown in the photograph below.

Filed in 70s Housing, Buckinghamshire, Education, Housing, Milton Keynes, Modern Architecture, New Town, Private Housing, Schools, Social Housing, Town Planning

Tags: Derek Walker, Housing, Milton Keynes, MK North, MKDC, Modern Architecture, Nigel Lane, Schools, Social Housing, Traditional Construction, Wayland Tunley

In early 70s, while the large scale housing grids were being developed on southern flank of Milton Keynes near Bletchley (Coffee Hall, Netherfield, Eaglestone, Netherfield have already been covered in my earlier Blogs) northern flank started slightly more cautiously and more traditionally.

Milton Keynes, was badly suffering from shortage of skilled labour and contractors due to its huge building programme and distances from existing conurbations. There were attempts to design housing by using simplified and if possible use factory built or repetitive elements of construction where possible.

The first housing scheme near Stony Stratford, Galley Hill, was nearing completion and DOE’s granted permission for the same contractor to continue working on Fullers Slade provided the work continued from first site to the second. This imposed a much reduced design period (almost two months) and resulted in a simpler layout and quick decision making. Long delivery periods for bricks made it necessary to use diagonal cedar boarding as external cladding and a concrete system using a box system of shutters was used on a standardised 3.60m module for all dwellings.

In retrospect you can notice the direct or indirect influence of Wayland Tunley working with Derek Walker. Pithed roofs and familiar building materials were used whenever possible. This was in contrast wit Grunt Group’s bold use of flat roofs and metal windows and cladding at Netherfield (Ralph Erskin at Eaglestone performed a similar function) which ran into all kind of technical difficulties and windows and roofs had to be changed to make the dwellings habitable.

The decision was taken to use simple terraces with houses of different sizes, generally following the contours of the site. An ancient existing mature hedgerow offered a natural anchor to the generous communal spaces around terraces. The stepped section offers maximum living accommodation on the ground level and daylight within the units also allowing sun to reach the private garden positioned on north-east side of the terraces.

After about 40 years use.

As usual the landscaping is wonderful. Some of the large trees perished during Dutch Elm disease but others were planted. Unlike unfortunate disunity/disfigurement/multi-colour additions and ad hoc alterations to individual houses within the terraces of Netherfield, it is a relief to notice that there is a satisfying unity of colours textures and window designs despite quite a few major alterations to exterior design at Fuller Slade.

I read quite a few reports about fire incidents in local newspapers of Milton Keynes (unfortunately social housing schemes are often involved), I can only assume that the possibility of spread of fires with timber boarding and lack of vertical barriers may have added to this problem and perhaps explain the resulting changes.

The clay tile hanging has replaced the timber boarding between the window bands, simple (and controlled coloured) fins have appeared between dwellings. There is a relaxed and easy going use of car ports, stores and sheds which are often modified but are not offensive by any means. Children and families enjoy the public spaces in a safe and relaxed environment.

I must find out the reasons for this positive use after seeing the terrible failures in housing in other areas. This may be due to different ‘owner occupation’ ratios or the imposed rules on the new occupiers to conform with some acceptable communal responses to retain some visual unity. It is also possible that there is a large proportion of dwellings under a housing association control which carries out its own maintenance. There is no doubt that the north and south divide has some lessons to offer in Milton Keynes.

Filed in 70s Housing, Architecture, Buckinghamshire, Housing, Milton Keynes, Modern Architecture, New Town, Social Housing, Town Planning

Tags: Ceder Boarding, Derek Walker, Fuller Slade, Galley Hill, Housing, Housing in Britain, Ken Gibbon, Milton Keynes, MKDC, Modern Architecture, Social Housing, Stony Stratford, Wayland Tunley

Great Linford Housing, Milton Keynes

February 8, 2011

For some strange reasons Linford Grid managed to produce more successful housing schemes than many other grids developed at the same time. This may be partly due to small parcels awarded to better known architects and possibly due to abundance of existing trees and hedges and some notable existing village buildings. This scheme by Brian Frost for 113 housing units in terraced and courtyard houses was like most schemes designed for rental housing and once again has mainly ended up in private ownership with all associated problems damaging the architectural unity of the original scheme.

The strength of terraced houses around the edges of the site is as powerful as ever despite the bruises and unfortunate alteration occasionally ruining the roof line and fenestration rhythms. The local planning office must take a more rigid line to stop this damaging process in most early housing schemes specially designed as unified communities which is gradually being destroyed.

The fair-faced concrete walls are still looking good and some inventive roof extensions in courtyard housing are logical and witty. The damaged soft clay vertical hanging tiles are easy enough to replace but the ownership problems are stopping even this to be carried out in most places.

The quality and variation of external spaces and circulation with good landscaping still retains the coherence and yet again proves that good intelligent, creative designs are street ahead of acres of soul-less Barratt/Wimpey type mass production of mediocrity currently sweeping the city and even the country.

The plans and B&W photos are attributable to AJ 23 January 1978. B&W photos by John Donat.

The colour photos were taken recently. This series hopes to cover most of the early significant housing in the new city in its early days of development.

Filed in 70s Housing, Buckinghamshire, Cortyard Housing, Milton Keynes, Modern Architecture, New Town, Private Housing, Social Housing, Town Planning

Tags: Brian Frost, Housing in Britain, Landscape, Linford, Milton Keynes, MKDC, Private Housing, Social Housing, Traditional Construction

Fishermead 1&2, Early Central Milton Keynes Housing.

December 30, 2010

Fishermead was developed at a higher density than that of housing in other areas of Milton Keynes. In this scheme the residential density range is 219-224 people per hectare. The result provides an interesting comparison with the draft government circular published in 1966 which suggested that the suburban densities could be raised to 120 persons per hectare where appropriate.

The Central Area consisting of nine grids including Fishermead was to house approximately 30,000 people, together with related local commercial, social and educational facilities. At the time of inception 75 % of dwellings were designed for renting and 25% for sale (this proportion is possibly reversed by now). Various reserved sites were retained for future growth and possibility of change. Because of the flexibility in the structure plan, it was hoped that the continuity, growth and change could be accommodated consistently rather than fortuitously.

The predominant housing form is three-storey perimeter development around the edges of 180 x 130 m grid enclosing semi-private spaces which are directly accessible from the gardens of the surrounding houses. These spaces provide protected, safe areas for toddlers’ play, sitting areas and landscaping. The back gardens opening into these spaces were originally designed with little visual protection resulting in under use due to lack of privacy but at first opportunity timber and brick walls started appearing almost excluding the visual connection between home and the landscape space in the middle. Architects realized the need for privacy in these higher densities and the fencing for 2nd phase offered more privacy to the tenants.

Family houses are built in terraces along the streets and the smaller dwellings are accommodated in corner blocks. Space is reserved at each corner to provide for possible future community use: shops, office, residents’ club room etc.

If you have seen my previous Blogs on early grids of Milton Keynes, you would have noticed there are lots of common factors at work to make this look like a ‘deprived’ estate.

At one time the property prices were rock bottom and people were not prepared to live here unless there was no other available option. The economical factors have made this estate a ‘honey-pot’ for recent Somalian migrant population in Milton Keynes. The original architectural intentions to obtain flexibility on corner spaces to cater for ever-changing future needs seems to be working. There are thriving grocery shops and fast food stalls in corner locations serving the specific needs of the currently occupying community. This gives a certain ‘cohesive’ feel to the place and in some ways comes quite close to Jane Jacobs’ ideas of communal living.

Once again the original dream of housing a burgeoning middle class community with ‘Habitat’ furnishings and ‘comfortable’ living had a head on crash with the arrival of ever-changing disadvantaged communities struggling to survive. If you are prepared to ignore the architects compulsion to follow niceties about correct appearances, colour matching, sympathetic alterations and litter in key positions, you would have to concede that the discipline and the rigour of the original design has done its job differently, but adequately to offer a safe haven to a distant community (among others) whose arrival could not have been further away from the minds of architects of this remarkable office at the time of designing this project.

PVC windows are the biggest destroyers of the architectural fabric, closely followed by flimsy asbestos panels as these buckle, fade or get damaged. The age old wish to put personal stamp of ‘ownership’ results in a Netherfield type ‘rainbow’ effect which goes against the intention of the original design. The overhanging eaves of added pitched roofs tend to softens the personal touches and strengthen continuity.

The poor maintenance of infrastructure and building fabric remains woefully inadequate but the landscape continues to give this area a real environmental boost basically because it mostly looks after itself. What a shame that before selling the properties some long term strategy could not be created in an attempt to encourage and help the new owners to understand their role in maintaining their houses to enhance the original intentions and consistency required for a healthy and safe community living in a nice place.

The poor maintenance of infrastructure and building fabric remains woefully inadequate but the landscape continues to give this area a real environmental boost basically because it mostly looks after itself. What a shame that before selling the properties some long term strategy could not be created in an attempt to encourage and help the new owners to understand their role in maintaining their houses to enhance the original intentions and consistency required for a healthy and safe community living in a nice place.

The B&W photos, plans and some of the information is attributable to an article by Michael Foster in AJ of 11th May 1977. Old photographs are taken by Martin Charles.

Filed in Architecture, Buckinghamshire, Housing, Housing in 60s, Milton Keynes, Modern Architecture, New Town, Private Housing, Social Housing, Town Planning

Tags: 70s Housing, Derek Walker, High Density Housing, Housing, Housing in Britain, Landscape, Milton Keynes, MKDC, Modern Architecture, Private Housing, Shops, Social Deprivation, Social Housing, Trevor Denton