Archigram to Banksy

February 24, 2013

I bought Archigram magazine as a student in 60s and being an ardent follower, attended as many of their events as I could at that time. Architectural Design used to cover their work regularly and had a big readership among students.

I have been putting occasional scanned images from my Archigrams on Flickr site since 2008 (before the Archival Project existed) and recently a Blog for Archigram Monte Carlo 1969 competition entry published in AD of January 1970. Both my Flickr site and Blog have no commercial slant and simply aim to bring Archigram (and other architectural work of note) as a study resource easily available to the new generations of architectural students and teachers every where in the world, who may know little about the scope of their work and tremendous impact this group made on second half of 20th century.

Having a quick look at the ‘views’ recorded for my Flickr and Blog site for Archigram’s work, I can confidently say that figure is around 50,000. The hits come in clusters and it is not difficult to guess the part of the globe (Papua New Guinea to Peru) where some architectural student class is currently studying some aspect of Archigram’s work by looking at the viewing records against the global time differences

I do ‘smell a rat’ when all of a sudden I am approached by a ‘publisher’ talking about ‘infringements of copyrights’ as I see some kind of profit motive lurking in the background. I know enough about these issues including character and purpose of my web sites at the same time I would hate to do anything to upset either the ‘Archigram Archives’, any original architects or their heirs who are the owners of the copyright. If any of these find any use of the images on my sites offensive, damaging or unacceptable in any way, please write to me as I would withdraw any offensive image or make suitable amendments.

‘Slave Labour’photo by Nigel Howard for London Evening Standard.

Arcives are here: http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/

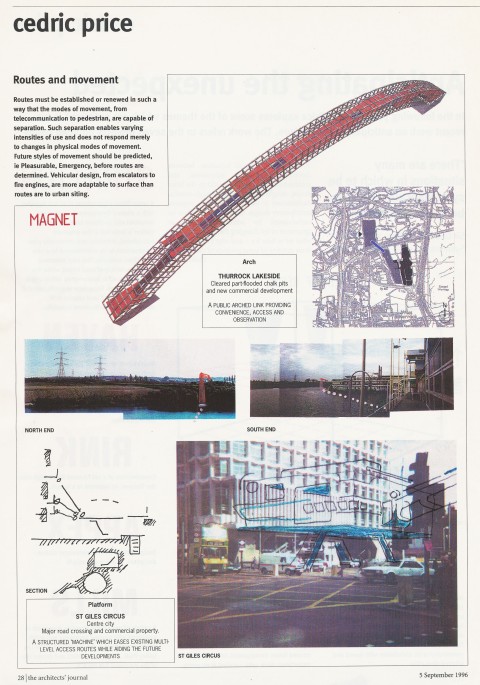

Cedric Price, Anticipating the unexpected, Magnets.

October 29, 2012

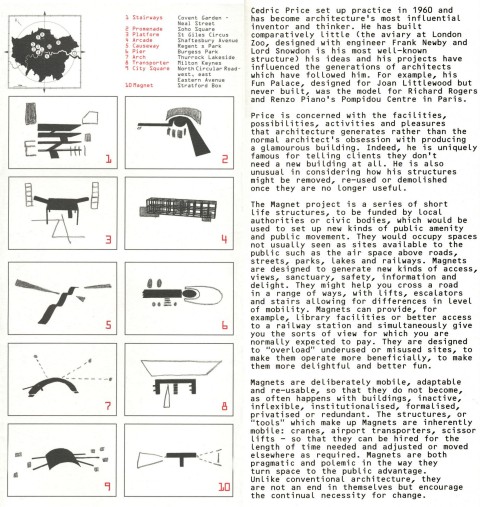

Towards the end of 1996 Cedric Price explored seven projects on the theme of anticipatory architecture, which were published in Architects’ Journal of 5th September 1996. This publication was followed by an exhibition called ‘Magnet’, arranged by The Architecture Foundation held in London from 18th April to 8th June 1997.

There is hardly any point in writing anything as an explanation or summary for Cedric Price, a difficult enough task for expert architectural writers, but in my inadequate hands it will be nothing short of a disaster. My thank to AJ and Kester Rattenbury for borrowing the abstracts from their writings.

As promised at the end of February 2013, I welcome the spring by removing all the images from this Blog I uploaded at the end of July 2012. This saddens me but is to conform with the note received from Archigram Archives representative on 22 February 2013 (see below) about the use of copyright materials, a fact which is undeniable. However, my intentions were simply aimed at offering an open learning resource, sharing original Archigram intentions, when I as a student, bought the original magazines for pennies. In todays world these would have been available as a free/open resource for downloading on Internet.

I intend to revisit this Blog in future after studying the background of the competition and looking at some of the social/political changes which were taking place at that time eventually leading to the cancellation of this as a viable project.

This was a limited competition for an entertainment and sports building on the reclaimed foreshore of Monte Carlo. Archigram reached the final stage and came very close to building in this glamorous city to provide the vibrancy displyed in their graphics.

The Brief required a multi- purpose space to cater for large banquet; variety shows, a circus, Ice rink and cultural activities were also eagerly sought. Architects noticed the lack of a public park and this beach side proposal could extend its services but remained complimentary in atmosphere and experience.

David Greene’s Rockplug/Logplug acted as an inspiration, grassy bank with trees placed over the hole in the ground livened up this depressing area, while offering a glamourous setting as illustrated by liberal use of scanty clad women armed with sun glasses, and a grid of plug-in points for headphones and other modern paraphernalia livening up the site to fit in the famous city of Monte Carlo. All the major functions brief required were housed in a large circular space chosen for its structural properties, covered with a shallow dome hidden under grass, offering extensive supports for all the technoligical kits Archigram could provide to improve upon Cedric Price’s Fun Place and Piano Rogers Beaubourg project.

The aim was to provide a large enough space for banquets, elephants or go-karts; adapting from chamber music to ice hockey. A place where the envelope and architecture was to become subservient to events and the structural systems and services providing magic tricks for multi-use were only playing the ‘second fiddle’.

The buried space was served by six entrances, each show making its own environment, organization and circulation patterns.

Most of the facilities like toilets, normally built-in were designed to be mobile, using a comprehensive set of kit of parts, set at a 6m metre grid and gantries. The aim was to design a place not dissimilar to a live television studio, not unlike ‘Instant City’ in one location. No dividing line between performance and transmitted event (projection, overlay of media). Even after frequent visit to these activities, the visitors may not be able to appreciate the size or configurations within this large cavern.

An architecture that was to be made of the events rather than the envelope as it is likely Archigram considered Beaubourg was.

Peter Cook, Dennis Compton, Colin Fournier, David Greene with Ken Allison, Diana Jowsey, Stuart Lever. Engineered by Frank Whitby.

PS: I am informed that Ron Herron worked on the competition albeit whilst he was in America and consequently on the unbuilt scheme.

The information and original scans are attributed to an article in Architectural Design 1/70 Cosmorama

Cedric Price, Influential architect and theoritician.

December 5, 2011

Archigram is well known and its influences on architectural world are clearly understood and illustrated. The name of Cedric Price (1934-2003) is often heard in Archigram circles as he was close to the group and took active part in discussions and even contributed but was never a formal member.

He was born in Potteries his father was an architect who specialised in Art Deco Cinema design. Cedric Price was trained at Cambridge and AA where he also taught influencing many architects, Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, Will Alsop to name a few. He also worked for Maxwell Fry & Denys Lasdun before setting his own practice to build Aviary for London Zoo. He built very little but like many other thinkers had tremendous influence on future direction of architecture which continues to this day.

He was a believer in “calculated uncertainty” where adaptable, temporary structures were preferred. He believed that an ‘anticipatory architect’ should give people the freedom to control to shape their own environments. All buildings according to him should allow for obsolescence and complete change of use. Will Alsop, who worked for him in early 70s recalls CP’s delight in designing a Cafe for Blackpool Zoo which was eventually to be turned into a giraffe home. This fitted perfectly into his themes of uncertainty, adaptability and change.

In his ‘Thinkbelt’ University project he proposed simple, moveable buildings which would deliver education “with the same lack of peculiarity as the supply of drinking water.”

His most influential project was ‘Fun Palace (1961) ‘ for Joan Littlewood. It was killed off by local government bureaucracy. The design of Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s Pompidou Centre in Paris is called a direct descendant. Soon after that he designed ‘ Potteries Thinkbelt (1964)’ which still makes great deal of sense. Among his built projects only Aviary in London Zoo remains, as he ensured that the other temporary structure for a community use ‘Inter-Action Centre’ in Kentish Town was not listed but demolished as intended. It is also amusing to recall that he was the only architect who was a fully paid-up member of ‘Britain’s National Institute of Demolition Contractors’.

“Aviary was designed for a community of birds and his idea was that once the community was

established it would be possible to remove the netting . The skin was a temporary feature: it only needed to be there long enough for the birds to begin to feel at home and after that they would not leave anyway. ………Price the theoritician, functionalist was frightened of and avoided style. …. he wasn’t interested in being remebered. He was building a memory.” 1*

Later in his life he worked on ‘Magnet City’ which was an exercise in using intermediary spaces in London urban landscape to stimulate new patterns and situations for urban movement in the city. shown in an exhibition in 1997.

He also contributed to the ‘Non-Plan’ debate with Paul Baker and Peter Hall. This basically was an ‘anti-planning polemic’ which resulted in the formation of ‘enterprise zones’ like Canary Wharf in London and ‘Metroland’ in Gateshead. On personal level I never came to see great sense in this reaction against the previous planning failures and put in their this ‘free for all’ American style money making system even if it generated big business and attracted lots of users.

1* Will Alsop’s recollections.

Photo above shows three views (interior & exterior) of Fun Palace by Cedric Price 1962.

Stirling, Olivetti and Postmodernism.

January 10, 2010

A lot has been written about James Stirling and his journey from modernism of his ‘red buildings’ to postmodernism of No1 Poultry and since I lived through this rollercoaster period, desperately trying to follow these inexplicable twists and turns, I think time is ripe for me to look back and attempt to discern some hidden logic for this strange journey.

Understanding some of the personal traits of Big Jim, and reading anecdotal tales which abound, attempting to discover any linear development where there is a predetermined slot for all his creative activities would be futile.

There is no doubt that he was a brilliant designer, who always guarded his ‘creativity’ against any attempt to stop him reaching his clear goal of the end product, which he always crafted after thoroughly studying the given brief and context. Any attempt by the clients to change any aspects of presented design was never well received. This I discovered did not happen only after he acquired an international reputation, as Jim was equally hostile to even minor suggested changes on his very first scheme at Ham Common housing in late 50s.

It is said that the staircase leading to Jim’s office were lined with letters of complaint and dismay from clients and users of buildings and displayed proudly as badges of honour giving ample warning to any unsuspecting newcomers.

I am of the opinion that two closely spaced events may well have been the precursor of a major shift in the direction of his creative process; one was buying Thomas Hope’s furniture and second was to employ Leon Krier. These events coincided with the period when he was involved with Olivetti towards the end of 60s and early 70s.

Colin Rowe draws our attention to a perspective drawing (I think that there were at least two) that Leon Krier drew in 1971 for James Stirling’s un-built Olivetti Headquarters at Milton Keynes.

This drawing was meant to be homage by this young draftsman to his master, hinting at his interests in Thomas Hope’s furniture and also history. Stirling sits in his beloved chair, slightly outside the frame of the perspective, with an open book at the table in front, assumed to be a volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre complete. Leon Krier depicts himself as a classical bust looking at the whole scene. Jim is ticking off some young office junior, who, judging by his body language could not care less.

The style of drawing is reminiscent of Le Corbusier and also various other 19th-century neoclassical architects Jim acknowledged being influential for him. Thomas Hope also produced engravings in this style for “Household Furniture” showing neoclassical furniture.

Olivetti Training Centre project came to Stirling on recommendation of Kenzo Tange. I feel that Scarpa and Corbusier’s previous connections with Olivetti would not have gone unnoticed by Jim. Edward Cullinan was asked by Jim to take care of the renovation of the existing Edwardian building and he started to work on the design of the new wing. This was to be his first and the last project where the design is influenced and inspired by clients work. It must be remembered that at that time Olivetti held a place in industrial design world not dissimilar to ‘Apple’ today. Their streamlined colourful injection moulded products were trendy and coveted items.

It is interesting to note that this is one of the few projects from Jim’s office where the building failures and defects of the completed projects have not been brought in the public domain. It is possible that these were not present or it can be assumed that a well-off corporation would quietly take the appropriate steps to resolve any problems as these arose. After all, for them to have a building designed by an international celebrated architect was like a prize business card.

The design of Headquarter building in the new city of Milton Keynes followed the completion of the Training Centre. Unfortunately the computer age had greatly undermined Olivetti’s market position and the HQ was never built.

It is clear that this time Stirling firmly decided to steer away from client product based design and went back to his own familiar way of using various historical and contemporary references to other architects and his own buildings.

Kenneth Frampton suggests ‘evidence can be found of the roof of Leicester but flattened, the tented greenhouse roof of the History Faculty, and the urban galleria and circus hall of Derby City Hall. Outside influences include Aalto’s staircase wall of his Jyvakyla University of 1950, Niemeyer’s organic dance pavilion at Pamphlua in 1948, to Le Corbusier’s Olivetti Computer Centre, projected for 1965. Instead of the singular industrial design references, Stirling is back to his own court.’

Mike Girouard noted that Krier’s … “outline drawing take objects out of space and time into a Platonic world of pure form, undisturbed by accidents of texture or light and shade.”

He thought the impeccable quality of the lines unify the disparate elements represented, helping the viewer to apprehend the underlying qualities that unite a chair by Thomas Hope with Stirling’s design for the Olivetti Headquarters at Milton Keynes.

Was this drawing ‘watershed’ announcing the arrival of “Postmodernism” in Stirling’s work?

PS. A quick look at the time line shows that the work in next ten years or so was; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Sackler, Wissenschaftszentrum, Clore. some of this work can be seen here http://www.flickr.com/groups/675480@N22/